The fork fell from my hand and rang off the plate like a tiny bell. The sound sat between the candles and the flowers and the roast like a little truth that refused to leave.

“What money?” I asked. “Grandma, I haven’t received anything from you. Not since I started college.”

Chairs creaked. Napkins stilled. Eyes tipped toward my parents as if pulled there by a tide.

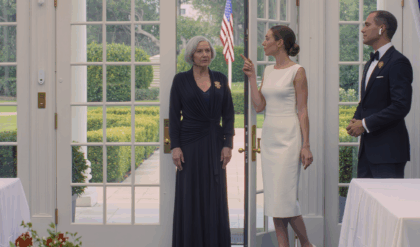

“Robert. Elizabeth,” Grandma said—my father first, then my mother—the way she said names when she meant business. “Would you care to explain?” Her voice was not loud, but it had the clean edge of a knife you use only on holidays.

“Mother, this is complicated,” Mom said, her smile wobbling. “Perhaps we shouldn’t—”

“I have nothing to be ashamed of.” Grandma didn’t blink. “Tell us what you did with Amanda’s money. And if you don’t tell us everything right now, I’m going to the police.”

Mom’s mascara blinked wetly. Dad studied his empty bread plate as if the answer were printed on porcelain. “We—we’ve been using the money for Henry,” he said. “He has a gambling problem. He got mixed up with the wrong crowd. We tried therapists, clinics—he keeps relapsing.”

The old reel flickered to life: Henry’s car keys flashing in the sun on his sixteenth birthday while the neighborhood applauded; my yellow clearance‑sale bicycle two years later under the fluorescent hum of a discount store; the week of crackers and peanut butter when the café closed for sanitation; Sarah’s bowl of microwave rice sliding across our desk; my laptop wheezing and dying at midnight. I had believed Grandma had forgotten me. Shame and anger braided together, bright and clean.

Grandma rose, small and immovable. “Everyone, please enjoy the celebration without me.” She didn’t look away from my parents. “Robert. Elizabeth. My office. Now.”

They trailed down the hallway like children summoned to the principal. The door clicked shut. The room exhaled in awkward, sputtering sentences. My cousin Tyler put a hand on my shoulder. “You okay?” he whispered.

I couldn’t find a voice to borrow. In the hallway I pressed my ear to the office door. No shouting. Grandma’s even tone; Dad’s ragged replies; Mom’s hiccuping breaths. I caught only fragments—“years of lying,” “we thought we could fix it,” “you stole from a hungry child”—and stood there long enough for the carpet’s pattern to burn itself into my vision.

When my parents emerged, their faces were scrapped raw. They didn’t say goodbye. The front door made the quietest sound a slammed door can make.

Five minutes later Grandma returned, clapped her hands once, and said in a cheerful voice, “Who wants cake?” As if the sugar could bind what had split.

We ate lemon cake like it was a duty, forks lifting and setting down with liturgical obedience. When the last cousin left and the dishwasher hummed, Grandma took my hand.

“You’re not going back to your parents’ tonight,” she said. “Stay with me.”

Relief loosened a knot I hadn’t known I’d tied.

In the morning, she set two mugs of coffee on the table and a small, blue notebook between us. The kitchen window framed the maple in her yard, thin branches drawing tiny lines against the pale sky.

“You should know,” she said, “I never paid your tuition directly. I gave money to your parents because I trusted them—and because bank transfers have too many screens. You had a partial scholarship. Instead of the hundred thousand I set aside, it cost forty. They kept the extra sixty and used it for Henry.”

Heat climbed my throat.

“There’s more.” She met my eyes. “Henry never went to college. They sent him to a place called Riverdale to get him away from his friends. He found new ones with the same habits. I gave him eighty thousand for an education he didn’t take. And I’ve been sending fifteen hundred a month for almost two years for you. Your parents intercepted it.”

It didn’t feel like a blow. It felt like a rearrangement: the same room, all the furniture in the wrong place. A childhood you thought you understood, gently turned inside out.

“I’m so sorry,” Grandma said, laying her hand over mine. “I should have checked on you directly. That’s on me.” Then her shoulders squared. “Now we do it right. You study—that’s your job. I’ll send two thousand a month, directly. No more middlemen. Today we go to the bank so you can see every deposit on your phone.”

We did it by noon. We signed forms while a banker named Carla said “good choice” as if we’d just picked a particular brand of sunshine. On the way home Grandma made me buy a winter coat that actually closed and boots that didn’t let slush in. I stayed three days. We ate leftovers, argued amiably about Wheel of Fortune answers, and laughed hard enough to pause the show. When she dropped me at the bus station, she pressed a sealed envelope into my hand.

“Emergency only,” she said, eyes daring me to protest. “Don’t argue.”

Back at school, my life did not become easy. It became possible. I quit the content‑mill job. I kept the café on weekends because Mr. Patel came every Saturday at ten for Assam tea and a blueberry muffin and told me about the sparrows on his fence, and I liked knowing things like that. I bought a secondhand laptop from a doctoral student defending in May and a cheap desk lamp that made my side of the room look like a page still being written. I stocked my mini‑fridge with yogurt and blueberries and a carton of orange juice whose cap squeaked when I twisted it. I paid Sarah back to the cent and took her out for tacos besides.

Without hunger humming in my bones, my mind felt like a room with the windows thrown open. I slept. I learned. I remembered what I read. I joined a study group that met beneath a stained‑glass window in the library where a ship sailed forever toward a horizon no one had painted in. By midterms, I was the person who booked study rooms and sent out shared Google Docs—someone I had never had energy to be.

Two months later, in the stacks, someone tapped my shoulder. Grandma stood there with a grin that would have gotten us both detention in Catholic school.

“Surprise inspection,” she stage‑whispered. The librarian shushed her. Grandma mouthed sorry without looking sorry at all.

Over turkey sandwiches at the campus café, she delivered news the way other people remark on the weather. “I rewrote my will. You’re my sole heir.”

I stared. “What? Why?”

“Because your parents have already had more than a quarter of a million from me,” she said, identifying the pickle spear as if it were a suspect, “and because you turned hardship into character instead of resentment. It’s not about need; it’s about trust. I trust you to make something of it. Also, I told them. They’re furious. That’s the tax for lying.”

Gratitude rose so fast I went a little light‑headed. “Thank you,” I managed.

She waved that away. “Don’t thank me for correcting my own mistake. Just promise me you’ll let yourself want the real things. Not cars. Not showing off. A life you chose.”

A week later a knock brought the smell of my mother’s perfume to my dorm room. Sarah murmured something about calculus and slipped out.

Dad lowered himself into my desk chair like a man trying furniture for the first time. Mom perched on Sarah’s bed and laced her hands so tight her knuckles went white.

“We need you to talk to your grandmother about the will,” Dad said.

“No,” I said.

“Because we’re your parents,” he offered, the way one points out gravity.

“That didn’t stop you from stealing from me.”

“You don’t understand what we’ve been through with Henry,” Mom said. “Addiction is—”

“I understand that you lied,” I said, surprised by how level my voice sounded. “I understand hunger in a way I shouldn’t. I finished strangers’ leftover fries at the café because I was too hungry to throw them away. I wore the same three outfits for two years. I cried when my laptop died because I couldn’t afford to fix it.”

“You’re exaggerating,” Mom said quickly. “I’m sure it wasn’t that bad.”

“Not that bad,” I repeated. “I lost twenty pounds my first semester. Sarah loaned me money for food. Some days the room did the breathing for me.”

Dad switched tactics. “Just tell Grandma you’ve been fine. Tell her we supported you.”

“You want me to lie. Again.”

“We’re family,” he said, as if that settled anything.

“Family doesn’t ask you to lie to cover their theft.” I found myself standing. “You chose Henry over me again and again. Did it fix him?”

They had no answer they could say out loud and still be able to live with themselves.

“He’s our son,” Mom whispered.

“And I’m your daughter.” I opened the door. “I’m not changing Grandma’s mind. Live with your choices.”

“You’re being selfish,” she said. The word hit an old bruise and, for once, didn’t land.

“Please leave.” I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t need to.

When the elevator doors closed, I sat on the floor until my breathing matched the radiator’s soft knocks. Sarah returned with a candy bar and the kind of silence a person can live in.

From there, life widened by inches and then by yards. My psychology professor scribbled three exclamation points in the margin of a paper and asked if I’d considered applying for a research assistantship. Before, the answer would have been no; now I said yes and meant it. I learned SPSS and cursed it, then learned to like the way numbers tell the truth when you ask clear questions. On Sundays, Grandma called. We didn’t talk about my parents unless I wanted to. She told me how she grew up as “the middle child who held the ladder while everyone else climbed,” and how, eventually, she learned to climb, too.

In March, a cousin texted: Did you hear about your parents’ house? A call to Grandma filled in the rest. They had sold it to pay Henry’s debts. Loan sharks don’t send flowers. No one wins against the math.

“Do you want me to help them?” she asked.

I wanted to be the kind of person who said yes automatically. I also wanted to be someone who had learned something. “No,” I said. “They made their choice.”

Spring break in Miami wasn’t about the beach—though the sky was the particular blue you suspect is lying. It was about ordering the entrée I wanted without calculating a week of groceries. It was about laughing on a balcony at midnight with friends and not feeling like a guest in my own life. I bought a red swimsuit. I went parasailing. From up there, the coastline unscrolled like a map of a future that might actually include me.

When we got back, a letter waited in my mailbox. My mother’s handwriting tilted across the envelope the way it had on permission slips for field trips.

Amanda, we’ve moved to a smaller place. The address is below if you ever want to visit. Henry is in rehab again. The doctors think he might have a chance if he sticks with the program. Your father and I have been doing a lot of thinking. We made mistakes—big ones. We can’t change the past, but we want you to know we’re proud of you for standing on your own two feet. Love, Mom.

No apology. No ownership. Just a new address I had no intention of using. Sarah read it and rolled her eyes. “That’s it?” I slid the letter into the back of my desk and felt relief—a cousin of joy, speaking the same language.

By late April I was the sort of person who booked study rooms, who knew which bench saw the best sunset, who could name three different birds that visited the tree outside the library. Grandma visited again and took me to dinner. “How are you—really?” she asked over crème brûlée.

“Good,” I said. “Really good. I didn’t know life could be this uncomplicated.”

“That’s how it should be at nineteen,” she said, cracking the caramel with her spoon. “Your only job is to learn and grow.”

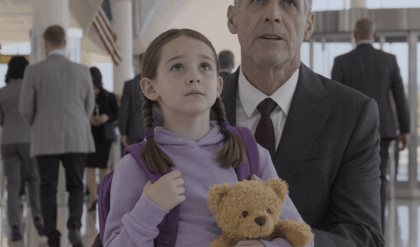

Finals arrived like a tide I could ride. One night, walking back from the library under trees that smelled like a sweetness I couldn’t name, my phone rang. Unknown number.

“Hello?”

“Amanda?” The shape of a voice I knew better from childhood than from now. “It’s Henry. I’m calling from rehab. Part of recovery is making amends. I didn’t know Mom and Dad were taking your money for me. That doesn’t make it right. I’m sorry.”

I sat on a warm stone bench and watched a couple cross the quad holding hands like it was a new idea. “No,” I said. “It doesn’t.”

“I’m not asking you to forgive me,” he said. “I just wanted to say the words out loud.”

We hung up. I stayed awhile. The library’s stained glass glowed from within, the ship still chasing its horizon. For the first time, I understood that “okay” is a place you arrive and claim. Not perfect. Not easy. Just yours.

Summer brought a small research stipend and a title that felt too big for me until it didn’t: Research Assistant. The project studied resilience in first‑generation students. I took notes on how people rebuild from what should have broken them. Most didn’t say “moving on.” They said: next. They said: meanwhile. They said: I made a plan and stuck to the boring parts. I watched their hands while they spoke—their rings, their bitten nails, the calluses that told other stories.

Grandma came to campus in July to watch me present a poster with too many words and a graph that made sense to exactly six people. She wore a navy polka‑dot dress like the one in the photo of her at twenty‑one—the day she demanded a raise. Afterward, in the diner by the bus station, she ordered cherry pie and asked what I wanted next.

“I don’t know yet,” I said. “Graduate school, maybe. Or not. I want a life that doesn’t feel like waiting.”

“It shouldn’t,” she said. “You’ve already done the hardest part.” She tapped the Formica between us. “You told the truth and let it change you.”

I don’t know what will happen with my parents. Maybe they’ll find their way back to themselves. Maybe Henry will stay sober. Maybe one Thanksgiving five years from now we’ll eat lemon cake that tastes like a chapter ending. Maybe not. Maybe the family I’m building now—Sarah; Mr. Patel with his sparrows; my lab partner who texts pictures of clouds that look like whales; the banker who remembers my name—is enough.

What I do know is this: the night at Grandma’s table wasn’t an ending. It was a door. On the other side is a girl with a notebook and a winter coat that closes and a bank account she can see on her phone. There is a grandmother who knows exactly how much leaves her hands and where it lands. There is a future that doesn’t require permission.

Whatever happens with my family, I’m not standing at the edge of it anymore. I’m in it. I’m moving. I’m okay—and when I’m not, I know what to do.

And because I promised myself to remember—not only the big scenes but the small ones that built them—I wrote it all down. The week the café closed and the crackers ran out. The first time Mr. Patel asked about my exam and I realized I wanted to tell him. The squeak of the orange‑juice cap. The banker’s pen scratching my name onto an account that was mine and only mine. The way Grandma’s hand felt over mine—warm and certain, like a key in a lock that had been waiting for the right turn.

That is the life I’m making: not dramatic, not flashy, but mine. A life with open windows and honest math. A life where the money that is meant for me actually reaches me. A life where I measure love by presence, not by purchases. A life where I can say no to the people who taught me I wasn’t allowed, and yes to myself when it counts.

It isn’t everything. It’s enough. And enough is exactly what I used to go without.

Fall arrived with the particular hurry that belongs to college towns—moving trucks idling at curbs, parents arguing softly over headboards, RA clipboards flashing like badges. By August’s end the maples on campus had already started rehearsing for October, one red leaf at a time. I biked past the dining hall in my new coat that actually closed and caught my reflection in a window: hair pulled back, face less hollow, posture that belonged to someone who expected to be allowed in.

The research lab kept me busier than any job I’d ever had. In a room that smelled faintly of dry‑erase markers and printer heat, I learned how to ask questions that didn’t bruise the answers. The study—resilience in first‑generation students—meant hour‑long interviews that unspooled entire childhoods. We offered a twenty‑dollar gift card and a bowl of wrapped candy; people slipped their stories across the table like folded notes in class.

A sophomore in a faded track hoodie told me about living out of his car for two weeks when a roommate bailed. A nursing major laughed until she cried describing the night she calculated whether to buy a textbook or antibiotics. A woman with lilac braids looked right at me and said, “Hunger makes you quiet.” I felt the week of the sanitation shutdown rise in my throat like steam, and I told her the truth: “It does.”

After interviews, I’d sit on the library steps and watch the afternoon rearrange itself, thinking about the ordinary heroics people perform while pretending they’re fine. Some days I wrote at the campus newspaper between data entries—an op‑ed about the student pantry that made three people email me to ask how to volunteer, a small piece about the shame tax on borrowing. I signed those with my full name. It felt like adding a rung to a ladder.

Grandma called every Sunday. She had taken to opening with the weather as if the sky were our shared calendar: “Clouds shaped like shoes today,” or “Your grandfather used to say October is the one month even liars admit the truth.” Sometimes she’d ask about the lab; sometimes about Mr. Patel’s sparrows; sometimes she just wanted to hear me breathing while she boiled pasta. We stayed off the topic of my parents, not out of denial but out of decision.

In September, Henry wrote. The envelope was plain, the handwriting familiar in a way that tugged. Inside was a letter on rehab stationery and a money order for eighty‑five dollars.

Amanda—

Dishwashing job. Eight‑fifty an hour. This is from my first two weeks after rent in sober housing and bus fare. I know it’s nothing. It’s not meant to fix anything. It’s just a thing that’s mine to do. Please cash it. If you don’t need it, give it to Sarah or a pantry or someone who does. Part of amends is keeping it simple. I’m trying to learn simple. —H

I carried the money order in my pocket for two days, feeling its paper weight like a steadying coin. On the third day, I walked to the bank and cashed it, then handed the cash to the student pantry director, who stapled the receipt to a thank‑you card and said, “Come stack canned beans with us sometime.” I did. Two Thursdays a month, I learned the quiet choreography of stocking and the language people use when they are asking for help without saying they are.

October brought the attorney.

“Don’t dress up,” Grandma said over the phone. “Just come.” Her voice held that bright efficiency she saves for errands that change lives.

Her attorney had an office with plants that looked better watered than people. The woman’s name was Rojas. She shook my hand like we were getting married to a plan. The documents she slid across the polished table lived in a vocabulary I didn’t speak: revocable, successor trustee, spendthrift provision, no‑contest clause. I read them anyway. Grandma initialed and signed with a flourish; I signed with a hand that felt both mine and borrowed.

“This is not a prize,” Rojas said, as if she’d read my mind. “It’s a tool. Tools ask to be used responsibly. You’re allowed to take care of yourself.”

On the way home, Grandma said, “I wanted you in the room so no one can ever pretend again that the money was a rumor.” At a red light she tapped the steering wheel and added, “And so you could learn the sound of your own name when it is taken seriously.”

We skipped the highway and took the long road that runs past the fairgrounds. The ferris wheel stood quiet against the early October sky, a bright circle waiting for its reason to turn. Grandma pointed and said, “Your grandfather and I got stuck at the top once. Best fifteen minutes of marriage we ever had.” I laughed, because her stories always arrive with exactly the right weather.

On campus, midterms arrived the way tide does—announced and unstoppable. I booked study rooms; I drew mind maps in ink that bled a little; I learned to bring almonds to lectures because hunger has always been louder than any professor. When I forgot and the old lightheadedness started to whisper, my phone buzzed with a deposit alert from Grandma, as if my name in my pocket had decided to argue back at my body’s old fear.

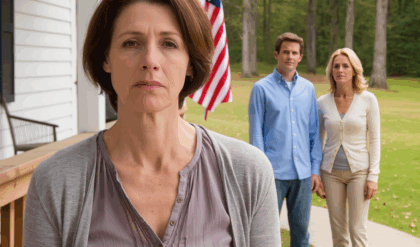

One cold Wednesday, a knock came at my dorm room that was not Sarah, not Grandma, not the RA. I stood with my hand on the knob long enough to decide something: I did not have to open the door. Then I opened it anyway.

My mother stood in the hall holding a small grocery bag like a peace offering. Inside were things that belonged to another season of my life: a scarf I’d left at Christmas two years ago, a mug from a school fundraiser, the sheet music I’d used when I thought I might keep playing piano. Her hair looked thinner; her eyes, more awake.

“Hi, Amanda,” she said. Her voice didn’t try cheap brightness. “Do you have a minute?”

“I have five,” I said, stepping into the hall. I left the door open behind me because I wanted the room to hear this.

“I came to apologize,” she said, and then paused as if testing the weight of the word in her mouth. “We took money that belonged to you. We lied. We made you hungry and tired and small. Nothing we did helped your brother. Most of it made things worse. I am ashamed of myself.”

I waited for the word but. It didn’t come.

She held out an envelope. “I can’t fix it. We are paying off debts we should never have created. This is what I could bring today.” Inside was a cashier’s check for three hundred dollars. Next to it, a typed list of planned payments and dates, all modest, all more than I expected.

“I’m not asking for anything,” she added. “Not the will. Not a conversation with your grandmother. I know better than to ask you to forgive me on my timeline. I just wanted to tell you I’m trying to learn simple.”

The phrase twinned with Henry’s letter in my mind, a small thread I had not expected anyone else to hold. I thought about the week of the sanitation shutdown, the taste of crackers, the way I had been taught to make myself smaller so someone else could fit.

“Thank you,” I said. “You can give this to the pantry.” I handed the envelope back. “They know what to do with money that saves people from hunger.”

She nodded, and for a second I saw the woman who used to braid my hair on the first day of school—concentrated, careful, trying.

“I’m in a program,” she said. “Family recovery. They tell us amends are a door, not a demand. I guess I’m knocking.”

“You can write,” I said. “Letters are better than visits right now.”

She didn’t cry. She nodded again and left, walking down the hall like a person who had finally looked where she was going.

I told Grandma about it that Sunday. She listened all the way to the end and then said, “Good. Keep your boundaries like a well‑built fence. They prove you love what’s inside.”

November is a loud beauty in our town—trees like lit matchheads, breath you can see leaving your mouth. I started waking early to run two slow laps around the track behind the gym. My body remembered being fed and, in gratitude, agreed to carry me farther. The lab offered me a second semester and a raise that felt like a full breath. I bought a pair of gloves that let me text without taking them off and mailed a pair to Grandma, who called to say, “These make me feel like a spy.”

Thanksgiving came like a test I’d studied for. Grandma invited exactly the people she wanted—Aunt Cathy, Uncle Luis, Tyler and his new boyfriend who made sourdough starters for fun, Mr. Patel (who brought a Tupperware of laddoo and looked very pleased about it), and two students from the pantry who couldn’t afford the bus home. We set the table with the good china. Grandma wrote place cards in a steady hand I could recognize anywhere. There was no place card for my parents. There was a quiet chair against the wall where they could have sat if there had been an apology I could trust.

We went around the table naming one true thing we were grateful for—no speeches, Grandma said, just the truth. Tyler said “the proof that I am more solid than the story I used to tell about myself.” Mr. Patel said “the sparrows are back.” One of the pantry students said “having enough.” When it was my turn, I surprised myself.

“I’m grateful for the word no,” I said. “It gave me room for yes.”

After dessert—yes, the lemon cake, tasting like a chapter that knows it’s not the last—Grandma and I washed dishes to the radio. She handed me a warm plate and said, as if talking about the weather, “I think I might sell the big house in the spring. Buy a little one near you. I can volunteer at the pantry and take classes if they’ll have me.”

I pictured her at the student center café browbeating freshmen into eating a second banana, at the bus stop wearing the spy gloves, in a classroom taking notes on a yellow pad as if she were being paid by the exclamation point. The future opened a notch wider.

December brought a letter from Henry with no money order this time—just words stacked carefully.

Amanda—

Still dishwashing. The manager says I can learn prep if I keep showing up. I go to meetings. I listen. I’m trying to give back to people I took from. I know you don’t owe me your attention. If you ever want to come to a family night here, it’s Wednesdays at 6. No pressure. —H

I went once. I didn’t tell anyone. Family night was a circle of chairs and a coffee pot that looked older than most of us. A counselor explained accountability as if it were a recipe and then asked us to go around and say our names out loud, even if we thought everyone already knew them. It felt, for a second, like a classroom where the lesson was being seen.

When it was Henry’s turn, he said, “I’m Henry, and I’m learning to do math that doesn’t lie.” He didn’t look at me until the end. When he did, he didn’t try to read my face. He just nodded once, as if to say, I know. I nodded back, which was neither forgiveness nor refusal. It was a placeholder for a future in which both of us might deserve more from ourselves.

Finals week ran like it always does: coffee like a ritual, libraries like sanctuaries, snow that decided to be dramatic exactly when no one had time. I finished my last exam, walked out into air that tasted like ice, and checked my phone. An email from the department—my stipend renewed for spring and a note from my professor: You have a rare ear for where a story starts. I wanted to write back that it started with a fork hitting a plate, or with a bicycle under bad lights, or with a grandmother saying, “Don’t argue,” but instead I wrote thank you and meant it.

Over winter break I worked extra hours at the pantry. On New Year’s Day, Grandma and I started a new tradition we invented in the kitchen at 9 a.m.: First‑Sunday Soup. Pot on, radio on, door open. Whoever needed food or company came by, no questions asked. Mr. Patel showed up with a jar of honey and a story about a hawk. Two students brought a chessboard. Tyler’s boyfriend carved the turkey carcass like an art project. No one mentioned my parents. Silence was not avoidance; it was a decision to let the empty chair be empty until it wanted to speak.

In January, a small envelope arrived postmarked from a town an hour away. Inside was a receipt from the pantry. In the memo line: In honor of the girl who kept a notebook of every debt. The donation was three hundred dollars. The handwriting was my mother’s. I folded the receipt and slid it into my own notebook where the page with Sarah’s $500 used to be. The line had been paid and then some.

Spring returned like it always does—mud on shoes, bright forsythia like a rumor of yellow. I turned twenty. Grandma mailed a card that played a tinny song when you opened it and a list of classes she wanted to audit: American history, statistics (“because I refuse to fear a bar chart”), beginner’s pottery. I wrote back: Take them all.

On the morning of my birthday, I ran two laps around the track and bought a grocery store cake for the lab and a bouquet of sunflowers for Grandma’s kitchen. When I got home from classes, there was a package at my door, no return address. Inside, a set of measuring cups, metal ones with engraved numbers that would never rub off, and a note in unfamiliar tidy print: Tools ask to be used responsibly. Happy birthday. —Rojas

I laughed out loud in the hallway, then cried in the nicest way a person can cry. The kind that is just gratitude finding a place to sit.

By April, the maples were rehearsing green again. I submitted a symposium abstract I was sure would be rejected and was stunned when it wasn’t. Grandma found a one‑bedroom on the bus line two stops from campus and negotiated like a woman who had not forgotten how to be twenty‑one in a polka‑dot dress. We moved her in three carloads and one city‑issued recycling bin; the spy gloves went in the top drawer by the takeout menus. She stood in the doorway at the end and said, “Well then,” which in Grandma means: cue the next chapter.

The first Sunday in her new place, we made soup and set out bowls. The pantry students took seconds. Tyler taught Grandma to play a phone game she immediately beat him at. Mr. Patel reported the sparrows had nested again; he swore they tilted their heads when he said my name. I do not believe this, but I like that he does.

Later, when the door was closed and the pot was soaking, Grandma handed me a small envelope. “Don’t worry,” she said, grinning. “It’s not money. It’s a list.”

Inside, in her careful hand: Things You Are Allowed To Want. It ran for two pages: sleep, a window that opens, a book you read twice, shoes that don’t hurt, love that doesn’t confuse, work that feels like work and also like worth, forgiveness when you choose, silence when you don’t, enough.

I taped it inside my closet where I’d see it every morning. I added my own at the bottom: a life that says yes when I knock.

If you need a date for when the story truly turned, you could choose the fork ringing off the plate. You could choose the banker’s pen. You could choose a money order for eighty‑five dollars, or an apology delivered without a but, or a soup pot that says come in. I choose the moment I realized I didn’t have to keep my hands out to deserve help. That I could say no to what hurt and yes to what fed.

The door at Grandma’s table didn’t just open. We walked through it. And on this side there’s sunlight on a small kitchen floor, and a measuring cup that says one cup and means it, and a calendar with the first Sunday circled in thick black pen—an invitation, a promise, a plan.