Part 1

After my millionaire grandfather died and left me everything, my parents—who had ignored me all my life—dragged me into court to take it back. The same people who never showed up to my birthdays, my graduations, or even my grandfather’s funeral suddenly remembered I existed when money was involved.

The morning of the hearing in Northern California, light cut through the tall glass windows of the Soma County Courthouse like a blade. The floor smelled faintly of polish and old paper. Shoes clicked across the tiles. Pages shuffled. Voices hushed to murmurs.

I sat straight, the collar of my dark suit stiff against my neck. The folder in my hand was worn from the night before, edges softened by the hours I’d spent reviewing the same evidence again and again. When I stepped forward, I didn’t look at them at first. I didn’t need to. I could feel their eyes before I even reached the defense table.

My mother, Lorraine, tilted her chin slightly and rolled her eyes—the dismissive gesture that had defined my entire childhood. My father, Trent, leaned back with his arms crossed, a smirk dragging the corner of his mouth. They thought this was already won.

The scrape of the judge’s chair cut through the silence. Judge Raymond Holt lifted his gaze from the file and froze mid‑page, his brow furrowed.

“Wait,” he said slowly. “You’re the defendant? You’re Assistant U.S. Attorney Dreven.”

The courtroom went dead quiet. My parents’ faces twisted in confusion, almost fear. My mother whispered something to her lawyer, probably asking what “Assistant U.S. Attorney” meant. My father stared at me, his smirk collapsing into something smaller, unsure.

“Yes, Your Honor,” I said, my voice steady. “Defendant in this civil suit and named beneficiary of Judge Elias Dreven’s estate.”

It felt strange saying my grandfather’s name in that room. The walls swallowed it, made it sound heavier than it should. He’d spent forty years in similar rooms across California, wearing the same robe Judge Holt wore now. The same robe that hung in my office closet—folded, waiting.

Their lawyer, a man named David Caroway, cleared his throat and began outlining their claim. “The plaintiffs, Lorraine and Trent Dreven, assert undue influence over the late Judge Dreven, claiming mental incompetence at the time the will was signed.” In other words, they were accusing me of manipulating my grandfather.

I looked down at the documents in front of me: notarized, airtight medical records from his physician confirming cognitive stability; my own records of visits every week, every Sunday dinner; a sealed letter addressed to me in his handwriting; and the bank statements—three thousand dollars wired to my mother every single month for over twenty years. More than eight hundred thousand dollars in total.

I had the truth. But truth is only as strong as the person willing to speak it.

Judge Holt shuffled his papers again, though he wasn’t really reading. I could see something flicker behind his eyes—recognition, maybe even guilt. Holt had clerked for my grandfather three decades ago. He knew the man’s precision, his iron memory. He knew that if Elias Dreven signed something, he meant it.

And yet, that recognition didn’t stop the weight pressing into my chest. Sitting across from my parents—two strangers who happened to share my DNA—felt like being dissected alive. They didn’t even know who I was. Not really. Ten years of law school, clerkships, prosecutions—none of it had reached them. Not one call, not one question. They never cared until caring came with a price tag.

When Holt scheduled the evidentiary hearing for thirty days out, his voice trembled slightly. The gavel struck, sharp against polished wood. My mother exhaled through her nose, triumphant, as if she’d already won. My father smirked again, smaller this time.

I stood, gathering my files. If they wanted to turn love into evidence, I thought, I’d let justice be the witness.

As I walked out, the chill from the marble floor climbed up through my shoes. The echo followed me into the hallway, and for the first time in years, I realized just how quiet blood ties could be when they’re empty.

Santa Barbara, California, 1993. My first memory wasn’t a face—it was rain.

My mother was nineteen then; my father, twenty‑one. They were chasing something brighter than parenthood, louder than responsibility. One morning before dawn, they left me on the porch of my grandparents’ house wrapped in a blue blanket. It was raining hard, the kind that blurred everything into gray.

My grandfather, Judge Elias Dreven, found me first. He’d been leaving for court when he saw the basket. He lifted me out, rain soaking through his overcoat. My grandmother, May, pulled me from his arms and pressed me close to the warmth of the kitchen stove.

“He’s freezing,” she whispered.

That house smelled of wood smoke and sugar. Every memory I have of childhood begins there: kitchen counters dusted with flour; the hum of old jazz on the radio; my grandmother laughing as I stood on a stool, trying to pour chocolate chips into cookie dough. I spilled more than I managed to mix, but she never scolded me. She just smiled and said, “The best cookies are the ones made with extra love and a little mess.”

There’s a Polaroid from that morning. I’m four, my face smeared with chocolate, grinning at the camera. On the back, in my grandmother’s looping script: Love is the only thing that leaves a beautiful stain.

For years, I believed my parents were just busy. My grandmother said it gently whenever I asked: “They’re doing important things, sweetheart. They’ll visit soon.”

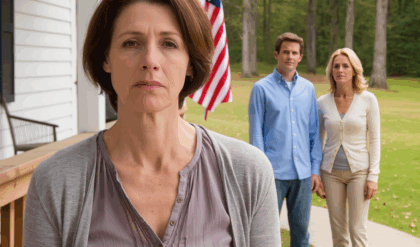

Kids believe kind people. So I waited—through birthdays, holidays, scraped knees. Sometimes my mother would glide in wearing perfume heavy enough to fill the whole room, her phone pressed to her ear. My father rarely came inside. He’d wait in the car, engine running, tapping the steering wheel like he was counting down the minutes.

Christmas visits, if they happened, lasted less than an hour. They brought shiny toys and no conversation. My grandmother would cook. My grandfather would try to keep the peace. But even then, I noticed the way he looked at my father—stern, disappointed, like a man who’d already seen the ending of a story and hated it.

When I was eight, my grandmother told me something she never meant to. She was washing dishes, talking half to herself.

“Your mother called once after she left you here. Not to ask how you were. She needed help with rent in Los Angeles.”

I remember asking, “Did Grandpa help her?”

“Of course,” she said quietly. “He always did.”

That was the day I learned generosity can be mistaken for forgiveness.

My grandfather kept a black leather notebook in his study. Inside were pages of neat handwriting—dates, visits, phone calls—and next to many of them a single word: missed. It wasn’t bitterness. It was record‑keeping—the habit of a man who measured the truth, even in his own family. Sometimes I caught him looking at that notebook before bed. He never spoke about it, just closed the cover and turned off the lamp. He never said my parents’ names in anger, not once. But silence can be sharper than any accusation.

As I grew older, I stopped asking when they’d come. I stopped setting extra plates at the table. I learned that waiting could be a form of self‑inflicted pain.

Years later, sitting in a California courtroom, those old rains echoed in my chest—the same cold, the same loneliness. The only difference was that this time I wasn’t the baby left on the porch. I was the man who had learned to stand in the storm.

I don’t hate them. I don’t think I ever could. But I’ve come to understand something my grandfather must have known all along: family isn’t defined by who leaves you, but by who stays. And in that simple truth, there’s a kind of justice no court will ever be able to rule on.

Part 2

Spring in Willow Creek, California, always smelled like wet soil and sunlight. The hills would turn soft green again, and the tulips my grandmother planted each year would rise in perfect rows—red, gold, and pale pink. The colors, she said, reminded her of reasons to stay.

That spring, I was eighteen, counting the weeks until graduation, when everything ended one ordinary morning. I found her in the garden just after sunrise. The coffee pot was still dripping inside, and she was lying between the rows, her gloves still on her hands, clutching a small cluster of bulbs. Her hair was dusted with soil, her face calm, as if she’d simply fallen asleep mid‑task.

I remember shouting her name, my voice cracking against the silence, and then the world blurred into sirens, flashing lights, and the smell of rain on fresh dirt.

At the funeral, my grandfather didn’t cry. He just sat through the service holding those same bulbs she’d meant to plant, his thumb rubbing away the dried soil. After everyone left, we sat together in the garden she’d left unfinished. I placed my hand on his shoulder and said quietly, “I’ll plant them, Grandpa. I’ll keep her garden going for both of you.”

He didn’t answer, but I saw the way his throat moved as he swallowed hard. That night, he left her chair at the dining table untouched. It stayed that way for years—an empty seat that somehow made the room feel whole.

We began a routine after that—Sunday dinners, just the two of us. Sometimes we ate her pot roast from the recipe cards she’d written in looping cursive, the edges yellowed and fragile. Sometimes we tried something new and burned it, laughing anyway. Those dinners became the quiet heartbeat of my life.

Her handwriting followed me everywhere. Inside an old tin box she’d left me were short notes on index cards: Don’t chase perfect; chase peace. You can’t teach kindness—only show it. I kept them tucked inside my law textbooks later—the kind of wisdom that didn’t come from lectures.

My grandfather changed, too. He still wore his judge’s robe and kept to his schedule. But something gentler moved beneath the precision. He began bringing me to his courtroom, not to show off, but to teach. He wanted me to see what calm looked like in the middle of chaos—the patience between questions, the silence before a verdict.

He told me once, “Law isn’t about punishment, Kalin. It’s about proportion. It’s knowing when to stop.” I wrote that down that night in my first journal: If justice isn’t kind, it’s only arithmetic.

By the time I left for Stanford, the decision to study law didn’t feel like a choice anymore. It felt like gravity. Still, every Sunday, no matter how far behind I was, I drove back to Willow Creek. Dinner with him was the one appointment I never canceled.

The night before I left for school, he called me into his study. The smell of old leather and cedar filled the room. He handed me a thick envelope, not heavy like cash, but dense with papers. Inside were annotated case studies, his notes in the margins, and a small brass key.

“This isn’t money,” he said. “It’s perspective. The key is to my office safe. One day, if you forget what you’re fighting for, open it.”

I nodded, tucking it away without asking questions. As I turned to leave, he added something softer: “There’s another envelope inside, sealed in red. For you—only when your conscience is tested.”

I didn’t ask what he meant. Back then, I thought I’d never reach that kind of crossroads. Years later, I would find out how wrong I was.

I left for Stanford the next morning, the sun still low, the garden glistening with dew. As I drove down the long dirt road, I looked back once. My grandfather stood on the porch, one hand raised, the other resting on the post where tulips would bloom by spring. I carried that image into every classroom, every courtroom, every moment that tried to shape who I would become.

I began my career wrapped in the armor of logic. But no matter how far I went, the smell of earth and tulips followed me. It was the scent of where I learned that justice—like flowers—only grows if someone keeps tending it.

The summer heat in Sonoma County arrived early the year my grandfather died. I’d been buried in cases at the Department of Justice in San Francisco and hadn’t made it back to Willow Creek for six months. When I finally drove up the long gravel road, the grass was overgrown and the tulips had withered into pale husks. The house looked smaller than I remembered.

“He died in his sleep,” the caretaker said. Peaceful, they told me, as if that softened the blow.

Inside, the clock on the mantle still ticked, his coffee cup half‑empty beside the morning paper. The robe he’d worn for forty years hung over the back of his chair, sleeves folded like waiting arms. On his desk was a single sheet of paper with my name written across the top in his steady, looping handwriting: Don’t cry. We haven’t lost each other. We’ve only changed our seats in the courtroom.

The words blurred as I read them. I sat there until sunset, the house creaking around me, the silence pressing like a verdict I didn’t want to hear.

A week later, I sat in the office of his attorney on State Street for the reading of his will. I expected small things—a watch, maybe some books, the garden bench he’d carved with my grandmother. Instead, the lawyer looked up from the pages, cleared his throat, and said, “He left everything to you, Mr. Dreven. Five point eight million dollars. The Willow Creek Ranch. His investment accounts. His insurance. Everything.”

I remember staring at the lawyer, waiting for a correction. “That can’t be right,” I said. “He has a daughter.”

He handed me an envelope addressed in the same handwriting as the note. Inside was a letter written months earlier:

Kalin, what I leave you is not wealth but duty. You are to keep what matters honest. You will be tested. Use the law as a shield, not a weapon. Love will cost you. Justice will ask for proof. Be ready.

Behind the letter was a packet of documents—bank transfers, handwritten calendars, notes in his firm script. For twenty‑two years he had sent my mother three thousand dollars each month—over eight hundred thousand in total. I flipped through the statements, seeing his comments in the margins: Rent due. Another request. Said she’ll visit next month. Didn’t.

Every line was quiet evidence of a man trying to love someone who had long stopped listening.

There was also a small sealed envelope in the folder, written on the front: Open only if you are accused of betrayal. I didn’t open it. Not yet. The weight of the words alone was enough.

I looked at the last page of the will where his signature sprawled just above the notary seal. There was a final handwritten line added beneath—the ink fresher, the letters slightly unsteady: All remains to Kalin Dreven in gratitude for his loyalty and love. The date was four days before he died. I knew exactly how that would sound in a courtroom: a frail old man, perhaps confused, perhaps pressured.

Standing in that office, I felt both honored and condemned. My grandfather had prepared me for law, but I never imagined he was preparing me for this—being judged, not by strangers, but by the people who shared my blood.

As I left, the lawyer placed the sealed will in a brown envelope and handed it to me. “He anticipated there might be challenges,” he said gently. “He said you’d know what to do.”

Outside, the afternoon light burned gold across the vineyard hills. I drove back to Willow Creek and walked into the garden. The tulips had long been cut down, the soil dry and cracked. I knelt and touched the earth where my grandmother had fallen years before. The wind picked up, carrying dust and the faint scent of summer grass. For a moment, I almost heard his voice again—steady, calm, instructive: Justice isn’t about winning, Kalin. It’s about what you can live with after.

I looked toward the porch, imagining him there, coffee in hand, watching me the way he used to when I was a boy. He’d left more than property or instructions. He’d left a test—not of the law, but of me.

Part 3

The sky over San Francisco was the color of old concrete when the envelope landed on my desk. My secretary slid it toward me, the red court seal already breaking through the thin paper. The printer whirred; the smell of burnt coffee lingered from the morning rush. For a moment, I thought it was just another subpoena.

But then I saw my own name printed on the front, underlined twice. Plaintiffs: Lorraine and Trent Dreven. Defendant: Kalin Dreven. Allegation: Exertion of undue influence and emotional manipulation for financial gain against an elderly family member—Judge Elias Dreven.

I stared at it for a full minute before laughing once—quiet, short, almost polite. My parents, who hadn’t sent a birthday card in twenty years, had finally found a reason to remember me. Five point eight million dollars and a sense of entitlement dressed up as righteousness.

They were accusing me of manipulating the only man who’d ever shown up for me.

I closed the file, rubbed the bridge of my nose, and whispered, “Of course.”

The first thing I noticed in the complaint wasn’t the accusation. It was the signature at the bottom: David Caroway. I knew that name like a bad habit. Four years earlier, I’d prosecuted him for tampering with evidence in a securities case—Avalon Securities v. State of California. He’d been suspended from practice for a year. It had cost him his reputation and nearly his career. Now he was back, representing my parents.

The move was personal, not professional. Revenge disguised as redemption. And this time, he was aiming for the one place he knew would hit hardest—not my record, but my bloodline.

By noon, my name was on every major paper in California: Federal prosecutor sued by parents over inheritance dispute. My phone exploded with messages from colleagues, journalists, strangers demanding statements. The office issued a note about conflict‑of‑interest procedures and administrative leave. I was told to step away from all ongoing cases until the matter was resolved.

I’d spent my life inside courthouses built on discipline and control. Yet now my career was unraveling in the same language I’d once used to undo others. The irony didn’t escape me. I’d built my professional life on the principle that no one is above the law. And now I was being cast as someone who thought he was.

I called Clare Hensley that night. We’d worked together for years—sharp mind, no patience for theatrics.

“I need representation,” I said.

“You’re serious?”

“It’s my parents.”

She paused long enough for silence to speak for her. “Then this isn’t law, Kalin. It’s theater. They’ll play sympathy. A courtroom can mistake tears for truth.”

She met me in my office the next morning, hair pulled back, briefcase already open.

“You can’t defend yourself,” she said, flipping through the complaint. “Conflict of interest. I’ll take it.”

“They’ll lose on facts,” I said.

“They might win on feelings,” she replied. “The public roots for whoever cries on the stand.”

By afternoon, news vans were parked outside my building. Cameras wanted a story, not the truth: Estranged parents. California inheritance. Prosecutor turned defendant.

That night, I drove north to Willow Creek, back to the house where it had all started. The tulip garden was bare—just dirt and memory. I unlocked my grandfather’s office and pulled open the safe he’d left me. Inside were neatly stacked folders, each labeled in his handwriting. One stood out: Holt—private. Beneath it lay an old photograph—my grandfather, younger, standing beside Judge Raymond Holt, the same man presiding over my case. On the back, written in the familiar ink I’d grown up reading: The man who knows the final truth.

For a long moment, I just stared at that line. My pulse slowed. Holt hadn’t just recognized me that morning in court. He’d known exactly who I was and exactly what this case meant.

I locked the safe again and turned off the light. If justice was a game, then this was the last round—and my opponents shared my last name.

The courthouse in Moran was packed from floor to ceiling the morning the trial began. The air buzzed with whispers, camera shutters, and the low hum of speculation. Reporters lined the hallway, their microphones raised.

I walked in with Clare beside me. She looked composed. I didn’t. I could feel the weight of every eye tracing my steps. My mother sat in the front row dressed in black, clutching a tissue she hadn’t used. My father sat beside her, his face a careful mix of pity and triumph.

Judge Holt entered from the side door. His gaze brushed past me for a moment longer than it should have—something between recognition and warning. He adjusted his glasses, cleared his throat, and called the court to order.

Caroway started first. His voice was smooth, rehearsed, almost theatrical. “Ladies and gentlemen, this is a story of a son who turned away from his parents—who used his grandfather’s grief and failing mind to claim what was never his.” He gestured toward a large monitor. A photo appeared: me in my graduation gown at Stanford. Alone. “Notice who’s missing,” he said. “His family. Because for Kalin Dreven, family is useful only when it benefits him.”

The audience murmured. My mother dabbed her eyes. It was a performance—one she’d been rehearsing her whole life.

Clare leaned toward me. “Let him talk,” she whispered. “Truth doesn’t need to shout.”

Then came his second act. Caroway introduced a psychologist who claimed my grandfather had suffered from post‑grief depression after my grandmother’s death. “A man in that condition,” he said, “is easily influenced by those closest to him.”

Clare stood for cross‑examination. “Doctor,” she said, “have you ever met Judge Elias Dreven?”

He hesitated. “No.”

“Then your diagnosis is based on assumption, not observation.” She turned to the jury. “That’s not psychiatry. That’s storytelling.”

The room shifted. The doctor’s face drained of color.

But Caroway wasn’t finished. He called my mother to the stand. She walked carefully, pausing just enough to appear fragile. “He was everything to me,” she said, her voice trembling. “But after May died, he changed. He stopped calling. He let Kalin control everything.”

Clare waited for her to finish before rising. “Mrs. Dreven, you visited your father—how often in his final decade?”

Lorraine swallowed. “When I could.”

“Records show eight visits in ten years. Is that correct?”

Her eyes darted toward Caroway.

“I was busy—”

“And yet,” Clare continued, “your father transferred you over eight hundred thousand dollars during that time. Is that also correct?”

The courtroom went silent.

When she stepped down, Caroway’s jaw tightened. He reached for his next weapon—a letter. “Your Honor,” he said, “we present a handwritten apology from Judge Dreven to his daughter, expressing regret for being distant.”

Holt took the document, scanning it. “Is there an original?”

“No,” Caroway admitted. “Only this copy.”

Clare requested handwriting verification. The expert shook his head. “It’s inconsistent with known samples.” The lie fell apart under the weight of its own ink.

Still, doubt had been seeded. Holt leaned back, expression unreadable. I could feel the moment slipping away—the truth losing ground to performance.

That’s when I reached into my briefcase and pulled out the red‑sealed envelope my grandfather had left for me. My hands shook as I broke the seal. Inside was a small USB drive. I handed it to Clare without a word.

“Your Honor,” she said, “this is an authenticated recording dated three years before Judge Dreven’s passing.”

The room fell silent as the audio played. My mother’s voice filled the speakers—tired, sharp, unmistakable.

“I don’t want the boy,” she said. “I just want what’s owed to me.”

My grandfather’s voice followed, quiet but firm: “Lorraine, love isn’t debt. You can’t cash it in.”

Then her answer—cold as metal: “You always choose him over me.”

When the recording ended, the silence was complete. Even the reporters had stopped typing.

“My words were taken out of context,” my mother stammered.

Holt leaned forward. “I was present during that conversation,” he said, his voice steady. “Both parties were aware they were being recorded. The court accepts it as admissible.”

For the first time, I saw fear cross Caroway’s face. He opened his mouth, then closed it again.

I looked at my mother. “I never asked for anything,” I said quietly. “I just stayed when you left.”

Holt’s gavel came down hard. “Court will adjourn until verdict.” The echo rang like a closing door. My mother sobbed into her hands. My father sat motionless, staring at the floor. Clare touched my arm but said nothing.

Outside, cameras flashed. Reporters shouted my name. None of it mattered. The trial was almost over, but the ache inside me was just beginning.

In the reflection of the courthouse glass, I caught my own face—calm, controlled, unfamiliar. For the first time, I understood what my grandfather meant when he said justice would test me. It wasn’t about proving innocence. It was about learning how much of your heart survives the truth.

Part 4 (Final)

Fog hung low over the courthouse. Wind off San Pablo Bay cut through my coat as if the fabric were paper. I sat in the car with Clare and listened to my watch tick. Neither of us spoke. Outside, camera crews clustered at the steps—mouths moving, lights blinking—the story already written on their faces.

I breathed once, then again, and opened the door.

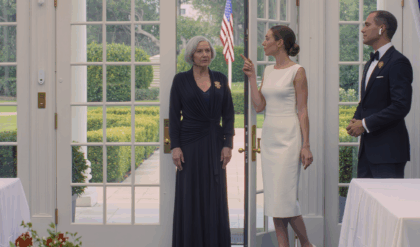

Inside, the gallery was full. My mother wore a black dress and the strained poise of someone who’d practiced looking fragile. My father sat a row behind, eyes raw, jaw set. Judge Holt took the bench, and the room stilled. On the far wall, a display case had been set up for the day—my grandfather’s robe draped on a stand, its sleeves falling like calm hands. Holt saw it too and gave the smallest nod before striking the gavel.

“The court has reviewed the original will, the medical records, the sworn testimony, and the recording between Judge Elias Dreven and Mrs. Lorraine Dreven,” he began, his voice even and resonant. “These materials demonstrate that Judge Dreven remained fully competent and intentional in leaving his estate to his grandson.”

He turned his attention to my mother, then to me. “The court also observes a pattern of inconsistent contact and the misuse of trust by the plaintiffs toward the decedent.” He paused and signaled to the clerk. A sealed packet was brought forward.

“A supplemental exhibit was filed with the will,” Holt said. “The court will open it now.” Paper cracked in the quiet. Holt unfolded a letter dated three years earlier, written in my grandfather’s hand. He read aloud: “If my daughter and her husband should one day contest this, tell them they have already received enough—twenty‑two years of support, twenty‑two years of absence. What remains I give to the child who stayed.”

The room shifted—air moving, throats clearing, the dull scrape of a chair. My mother’s body sagged. She covered her face with both hands.

Holt set the letter aside and looked to me. “Mr. Dreven, you may speak.”

I stood. My voice felt like it belonged to someone else—steady, restrained. “I never asked them to care for me,” I said. “I only wanted to protect the dignity of the man who taught me that the law isn’t revenge. It’s how we guard love from being twisted into something it isn’t.”

I turned back to the bench. “If I have any power today, it’s because my grandfather taught me to use it for fairness first.”

Holt folded his hands. “This court finds the will valid in every respect. The complaint is dismissed with prejudice. Costs and attorneys’ fees are awarded to the defendant.” He let the words sit a moment longer, then added, “Care is not evidence of wrongdoing. In this case, the defendant’s conduct reflects filial duty, not manipulation.”

The gavel struck, and the room exhaled at once.

Reporters swarmed the aisle. I kept my eyes down and pushed through the corridor until the crowd thinned. Near the exit, my mother waited—shoulders small, mascara clouded at the edges.

“Kalin,” she said, almost a whisper. “I’m sorry. I just wanted to be close to you again.”

“You had thirty‑two years,” I said. I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t need to. I turned away. Behind her, my father stayed still, hands in his pockets as if rooted to the tile.

Outside, the wind came harder, bringing the briny smell of the Bay and the dry grass from the hills. I walked past the cameras and kept going until the only sound was my own breath.

On the drive north, I pulled onto a turnout and let the engine idle, windows down, air cold on my face. Relief didn’t arrive in a rush. It came like a weight loosening, knot by knot. I watched the water until the light broke through the fog. For the first time in months, I felt a room open inside my chest.

I’d won. And still there was no one to clap me on the back, no hand to shake across a dining table. Maybe real justice always leaves you with a little loneliness—a reminder you didn’t trade your heart to get it.

Three years later, I raised my right hand and took the oath. At thirty‑five, I became a federal judge in the United States. On the first morning I took the bench, I slipped into my grandfather’s robe. It was heavier than I remembered, the lining smelling faintly of cedar and old paper. A letter from Holt waited on my desk when I returned to chambers: A legacy continued. Wear it well.

My life narrowed in the best way—cases, chambers, long days stacked with long decisions. But Sundays never changed. I still drove back to Willow Creek, parked under the same oak tree, and knelt in the garden. Each spring, I planted tulips along the fence until the slats looked stitched in color. Neighbors sometimes waved from the road. I waved back and kept my hands in the soil. It felt like a prayer.

One afternoon, an envelope arrived from my grandfather’s former law firm. They had been cataloging archived materials and found an unsent draft addressed to my mother. The letter was dated years before he died. He wrote that he cared for her and always would—but that care was not a substitute for showing up. He wrote that he would not confuse forgiveness with forgetting.

I read it at the kitchen table where my grandmother used to lay out cooling racks for cookies. The house creaked. The clock ticked. For the first time since the trial, I felt something give way—anger loosening into a quieter sorrow.

Not long after, I drove to the cemetery in Marin. Someone had left a cluster of white tulips on my mother’s headstone. My father’s plot beside hers held only dust and a faded ribbon. I placed a bunch of yellow tulips between them and said softly, “I’m not angry anymore.” The wind lifted and fell. No answer came, but none was needed. The past felt less like a chain and more like a story I could finally put back on the shelf.

That fall, I set aside a portion of the estate and established the May and Elias Dreven Foundation—scholarships for law students raised by single parents and grandparents in the United States. At the dedication, I spoke without notes: “Family isn’t where we’re born. It’s where we’re chosen—daily. May this help someone keep choosing.”

I looked out at the rows of students and saw my younger self among them—tired, hopeful, trying not to show the hurt.

On a late Sunday, after the guests were gone and the hills were turning the color of copper, I unlocked the safe in my grandfather’s office one more time. Only one page remained in his hand: If you’re reading this, you understand the law isn’t where justice ends. It’s where a life worthy of it begins.

I folded the note and slipped it into the inner pocket of the robe. Dusk reached in through the windows as I walked out to the garden. The tulips caught the last light and held it like small lanterns. I sank to my knees, pressed my palms to the dirt, and breathed. The house behind me was quiet—the kind of quiet that doesn’t feel empty.

I’ve lived long enough to learn that blood gives you a name, and actions give you a home. My grandfather had been right all along. Care doesn’t need proof—only presence.

I stood, brushed the soil from my hands, and headed for the porch. The old wooden sign over the steps had weathered to a soft gray, the carving still clear:

Willow Creek Ranch — Where Justice Lives.

-End-