Part 1

(Chicago, Illinois, USA — high‑rise residential tower overlooking Lake Shore Drive and the downtown skyline.)

Thanksgiving’s full. Maybe next year.

The text made me laugh—short, cold, incredulous. So I ordered dinner for 120 people on my roof instead. I assumed they wouldn’t notice, but when that stretch limo rolled past the residents’ Bentleys at the front drive, my grandmother stepped out holding a single piece of paper, and my entire family froze.

My name is Aurora Lawson. I am thirty‑three years old, and I’m the founder of Falcon Route. If you received a package anywhere in Chicago in the last forty‑eight hours, there’s a good chance my platform optimized its last‑mile journey. I build systems that find the most efficient path.

I was standing in my penthouse on the forty‑eighth floor, looking down at the evening gridlock on Lake Shore Drive, when my phone vibrated on the black granite countertop. A text from my father: Richard. “Thanksgiving’s full. Maybe next year.” Eight words. I read them twice. A small, cold laugh escaped my throat. It wasn’t humor. It was recognition. The inevitable, finally arriving, stated in plain text. I typed back two words:

No worries.

“No worries” was a shield. It was the polite veneer I had perfected over three decades. It was the armor I wore to cover a lifetime of being asked to sit at the folding card table—the one shoved in the drafty corner of the living room—while the “real family” sat at the polished mahogany table.

My penthouse is sparse. Not warm—functional. The kitchen isn’t a “chef’s kitchen” the way magazines use that phrase. It’s an industrial‑grade setup: stainless steel, commercial appliances, efficient. It opens onto a large rooftop terrace I’d winterized with a heavy‑duty glass greenhouse. The steel‑gray sky reflected off the panes.

My family dynamic is simple. My parents, Richard and Beth, orbit my older sister, Sloan. Sloan is the star. High‑powered attorney at a white‑shoe firm. She’s the one they brag about, the one who gets the center seat at the mahogany table. My younger brother, Noah, is the diplomat. His whole life is a balancing act of strategic neutrality. He lives in the middle, which means he never—ever—takes my side.

I closed the text. A memory hit fast, like a flash cut in a film: me at nine years old, holding a platter of rolls. The big table was full—laughter, wine glasses clinking. Sloan, already a teenager, holding court. My mother, Beth, laughing, her eyes locked on Sloan. “Aurora, honey, we’ve got you set up right over there,” my father said, not looking at me as he pointed. The wobbly card table with a paper cloth. A second cousin I’d never met and a great‑aunt already asleep. A metal chair. Cold.

I shook the memory away and picked up my phone. If there is no path, my algorithms build one. I opened our building’s internal management app—runs on a custom logistics framework I helped the developers design. I booked the terrace. I ordered four commercial field kitchens. Twenty high‑output patio heaters. Six hundred feet of weatherproof, warm‑spectrum lights. Plan B: Penthouse Thanksgiving.

I pinged my assistant: Mave. She understands efficiency.

Change of plans, I typed. I’m hosting. I need a guest list of 100. Find me 100 people who need a warm meal—prioritize Falcon Route drivers on the night shift. Add local hospital nurses, third‑shift security, the people working while everyone else is home.

A building notice popped up: a generic memo from the homeowners’ association (HOA). Reminder: per building regulations, all rooftop events are limited to fewer than fifty persons for safety and insurance.

I smiled, opened my secure drive, and pulled up the covenants—a two‑hundred‑page PDF. Section 9, sub‑clause B. I knew it by heart.

My phone buzzed again. A private message from Noah: “Hey, A. Just heard the plan. Sloan invited her whole associate team—the partners, everyone. Mom says the table’s completely packed. Guess it got hard for them to fit you. Sorry.”

“Got hard.” Not “we saved you a seat.” Not “we told Sloan to be reasonable.” Just logistics without empathy.

I looked across my vast, empty living room at my own dining table—a massive slab of reclaimed wood, seats twelve. I looked back at the city. “If their table is full,” I whispered to my reflection in the glass, “I’ll just build a new one.”

An email dinged from the building system—but it was personal. My neighbor in 4803, Mr. Duca. He’d been a TV chef once—PBS, I think. Retired now. “Miss Lawson,” his note read, “the smell of that veal stock you reduced last Tuesday was audacious. Perhaps a bit too long, but the clarity was professional. I hear the logistical hum of a large‑scale event through the walls. If you’re planning something significant and need counsel around a turkey, I am spectacularly bored. Let me know.”

I felt the first real smile of the day. A good variable.

I scaled to 120 guests. “Mave,” I messaged, “update: 120 seated, plus 30 meals for buffer/support. Lock the freight elevator for a 24‑hour block. Load‑in 0600.”

I opened the CAD render of the rooftop, dragging assets: a continuous line of tables—one unbroken chain. Heated tents at the ends. Electric roasting stations placed over reinforced load‑bearing points. I uploaded the schematic to building ops.

A social alert pinged. My mother, Beth, had posted a photo from last Christmas: her, my father, Sloan, and Noah in matching pajamas. I’d been in Singapore, closing our first international deal—also uninvited. Caption: “Feeling so blessed this Thanksgiving. Can’t wait to have our complete family all together. Gratitude is everything.”

Complete.

I muted her posts. Logistics, not emotions. One last message to Mave: “Rule for the night—no kids’ table. No overflow. No B‑list. Everyone who walks in is main table.”

The sun slid behind the skyline; the city lights clicked on. I had work to do.

I was eleven the first time I baked a pie by myself. I practiced the lattice crust for a week. Cinnamon, nutmeg, apples—the scent felt like pride. I carried the warm Pyrex dish into the dining room. The big table was already set, crystal gleaming, silver bright. My father poured wine. My mother adjusted a centerpiece. Sloan, bringing nothing, told a story about her debate team. I held out the pie. “I made this.”

My mother’s smile was brief and tight. “Oh, how rustic, Aurora.” She didn’t take it. She motioned to my great‑aunt. “Let’s have Aunt Marge try a piece first—you know her stomach is delicate. If she can handle it, it’s safe for the rest of us.” Polite laughter—casual dismissal. Aunt Marge took a suspicious bite. “It’s fine.” The pie was relegated to the kitchen counter. Hours later, when the main dessert was gone, slices were passed to the wobbly card table. Cold by then. I took a bite—the cinnamon I had measured perfectly tasted like dust.

“Maybe next year” became the running gag. Maybe next year Aurora will make varsity, my father would say while ruffling Sloan’s hair—already team captain. Maybe next year Aurora will get the lead, my mother mused after Sloan’s curtain call. “Not now” always meant “not you.”

I graduated high school as valedictorian. Sloan had graduated two years earlier—magna cum laude. My parents framed two photos on the mantel—one of me in my cap, one of Sloan. My mother hand‑wrote the caption on the silver frame: “So proud both our daughters are so smart.” Not valedictorian—just smart. Sloan’s achievements were itemized; mine were averaged.

The break happened the spring my acceptance letters arrived. Full scholarship—Stanford Engineering. Not just an offer—an escape. Tuition, room, board—covered. Freedom, printed on expensive cream cardstock. I ran into the living room waving the letter. Sloan was home from her Ivy League, complaining about an art history grading curve. I handed the letter to my mother. She read it. Her smile thinned. “Stanford, Aurora? That’s far. Are you sure you can handle being that far from home? You’ve always been so sensitive.” Not a question—a verdict. She wasn’t worried for me. She was worried I would be an inconvenience from two thousand miles away. Sloan looked up, annoyed. “Stanford—isn’t that where all the tech nerds go? Pass the remote.”

That was when the “no worries” armor fused to my skin. I didn’t argue. I didn’t cry. I nodded. “I’ll manage.” And I did. Full ride covers tuition; it doesn’t cover life. While Sloan networked at my father’s country club, I learned Python, then C++, then systems architecture. I worked the graveyard shift at a twenty‑four‑hour coffee shop near campus—burnt coffee and industrial bleach in my clothes. Exhausted, but building. Overload classes every term. Graduated in three years. My first off‑campus apartment had black mold creeping up the bathroom wall; I scrubbed it with bleach until my hands were raw. I paid my own rent. I never asked them for a dollar. Reliance was just another word for liability.

People ask why I chose logistics. It’s not glamorous. Not high‑stakes law. It’s systems, predictability. I chose logistics because a server doesn’t care who your sister is; an algorithm can’t be charmed; a data graph doesn’t light up because you’re related to the CEO. Code is beautifully impartial: it works or it fails. The purest meritocracy I’ve found.

Falcon Route was born in a rented garage in Palo Alto: me, three secondhand servers I rebuilt, and a routing algorithm smarter, faster, more adaptive than anything on the market. First client: a regional supermarket chain in Michigan’s Snow Belt. Their problem was simple—last‑mile deliveries hemorrhaging cash from spoilage, ice delays, bad routes. I integrated my system, spent three nights in the back of a refrigerated truck, tweaking the algorithm in real time. Weather data, traffic patterns, prioritized windows—after one month, spoilage dropped from fifteen percent to near zero.

For years Falcon Route was my successful experiment. Then the pandemic hit. The country stopped. Supply chains fractured. Suddenly last‑mile optimization wasn’t an experiment—it was a lifeline. My algorithm wasn’t moving avocados—it was moving medical supplies, ventilator parts, PPE. While the ports choked and highways jammed, my system found the open paths. The press noticed—Forbes, Bloomberg—“the unseen algorithm supporting Chicago’s supply chain.” They called me a disruptor, essential. I didn’t send the links home. I knew I’d get: “That’s nice. Honey, did you see Sloan was just named in 30 Under 30 by the local bar association?” My success was invisible—it wasn’t their kind of success.

With every new contract, I did something my adviser called insane: I moved fifty percent of my personal profits into a locked fund. I called it the Long Table Fund. I didn’t know what it was for. I just knew “maybe next year” had an expiration date, and I would set it. The fund grew—into millions. Last year on a rainy Tuesday, I signed a deal: a major logistics conglomerate wanted to acquire Falcon Route. They wanted the algorithm. I said no to a full sale and offered forty‑nine percent. I kept fifty‑one, the voting rights, the control. Their wire was absurd by any definition. I didn’t buy a mansion or a fleet of sports cars. I bought the entire forty‑eighth floor of a tower in downtown Chicago. Not for the view—though it’s staggering. For the airspace—high enough, private enough to build what I needed: a table with no head, where everyone has the best seat. That’s why I built the greenhouse on the terrace. Not for orchids—a proof of concept. With the right engineering, bread can rise in a blizzard. Life can thrive in a hostile environment.

Last week a single chair was delivered—not part of a set. A heavy oak armchair. Before it arrived, I had the woodworker carve something into the back just below the headrest—where only the person sitting could feel: For the one who felt unseen. I run my fingers over the letters every morning. I looked at that chair and made a promise: no more folding chairs. Not for me. Not for anyone I invite.

I finished mapping heater placement. An official notification from the HOA portal landed in my inbox at 8:04 p.m.—polite, sterile, predictable: pursuit to Article 9, Section 3, gatherings over fifty require written approval fourteen business days in advance. My request, submitted less than twenty‑four hours prior, was therefore denied. “We apologize for any inconvenience.”

Denied. Inconvenience. They were citing the rules—but I had helped rewrite the book when I purchased the penthouse. Back then, the covenants were a mess; I re‑architected their appendices and cross‑references. I opened the bylaws PDF and searched: Article 9, Section 3—the fifty‑person limit. Correct. But they forgot Appendix 9, Section 3(b)—the exception I insisted on: for recognized charitable events, provided the host secures a minimum $5 million event insurance policy, safety certification from a licensed inspector, and all necessary municipal permits for food and assembly.

They thought I was planning a party. I was executing a charitable operation. This wasn’t a negotiation; it was a compliance check.

Insurance first. I opened a new tab to a specialist event insurer we use for Falcon Route launches. Web form: 150 persons, outdoor, temporary heating, temporary cooking. Five minutes and a card charge later, a $10 million event policy PDF was in my inbox.

Safety next. I called the private fire and safety firm that certifies our warehouses. “It’s Aurora Lawson,” I told the on‑call manager. “Emergency: I need full inspection and certification for a temporary outdoor kitchen, electrical load analysis, fire suppression placement, and wind abatement—tonight, within three hours.”

“Holiday rate,” he warned.

“I’m aware,” I said. “Send your best. I’ll pay double.”

They were on the way. I pulled the structural engineering report I had commissioned before installing the greenhouse: reinforced steel terrace rated for 100 lb/sq ft. My plan with 150 people, heaters, kitchens: less than 25 lb/sq ft. I attached the letter to a new file.

Municipal permits—bottleneck. County health department was closed, but the online portal for temporary outdoor food facility permits was automated—if you had a certified food protection manager on record. I dialed my neighbor, Chef Duca. He picked up on the first ring. “What.”

“It’s Aurora in 4801. The HOA is trying to shut me down, citing food safety.”

He gave a dry, crackling laugh. “Food safety? Friendly reminder: someone microwaved fish in the hallway last week. I could smell the plastic. What do you need?”

“Your ServSafe number and digital signature on a temporary permit. I need you listed as professional sponsor.”

“I’ll do you one better,” he said, already moving. “I’m coming over with knives and a Class K extinguisher. And I’m bringing my utility cart. We’re not losing on a technicality.”

“Thank you, Mr. Duca.”

“Don’t thank me—just save dark meat.”

While I waited for fire inspectors, I drafted the operational plan. CAD open, depot brain on. Egress paths mapped—two wide lanes marked with battery‑powered emergency lighting. Fire extinguisher placement: one Class K every fifteen meters. Wind guards for the cooking line. I called my private security contractor—the same firm that protects Falcon Route depots at the port. “Four‑person team, six p.m. to midnight. This isn’t crowd control; it’s crowd flow. I want professionals who understand ingress/egress.”

“Understood, Ms. Lawson. A‑team.”

The fire inspectors arrived at 10:00 p.m.—fast, professional, impressed by Duca’s rigor. They tested GFCI circuits for the roasters, measured distance between heaters and canvas, reviewed the egress map. At 10:32 p.m., I had a signed certificate of safety compliance.

Now I assembled the weapon: a single twenty‑nine‑page PDF. Page one, cover letter invoking Appendix 9.3(b). Page two, articles of incorporation for the Long Table Fund—the charitable foundation I registered three years ago. Page three, the $10 million insurance policy—paid in full. Page four, safety certificate. Page five, the structural engineer’s report. Page six, the application for the temporary food facility permit. Page seven, Duca’s certifications and signed statement as food manager. Pages eight through twenty: operational plan—CAD diagrams, egress maps, wind abatement, security. Pages twenty‑one through twenty‑nine: the confirmed list of partner groups—Night Shift Nurses Union and Regional Transport Drivers League.

I addressed the email to the entire HOA board and cc’d two parties: the building’s retained legal counsel—forcing the board to route through their lawyer and the bylaws—and our city alderman, a quietly supportive public servant whom Duca had cooked for at a charity dinner last spring.

I pressed Send. Torpedo in the water.

They took forty‑five minutes to reply. Short, panicked, sloppy: “Submission received. Temporary denial issued pending further review.”

“Pending further review” is not an article number. I replied instantly: “Pursuant to Article 4, Section 2 of the covenants, all denials must cite a specific actionable breach. ‘Pending further review’ is not specific or actionable. Please provide the exact article I am violating. If you cannot, I’ll proceed under the charitable exception of 9.3(b). Regards, Aurora Lawson.”

Checkmate on paper. I had insurance, certification, permits, professional sponsor. They had feelings. I had documentation.

While they tried to find a rule I had missed, I moved. I recorded a two‑minute video walkthrough—an empty‑terrace tour with CAD overlays: “Primary egress here; K‑1 extinguisher here; certified electrical junction here.” “The Long Table—safe, compliant, necessary.” Mave pushed the host‑plus‑guest signup link to the Falcon Route driver network and the local nurses’ message board. We didn’t ask for volunteers. We asked for partners. Within three hours, all forty support slots were filled.

Inevitable: a text from Noah. “Hey, A, this is getting wild. The HOA memo leaked to the resident portal. Mom and Dad saw it. They’re freaking out. They say you’re making a scene just to embarrass them.”

“Making a scene”—same frequency as “maybe next year.” My very existence framed as inconvenience.

I looked at the orders: food, heaters, wool blankets for every chair, the lights. I typed back: “Only color tonight will be warm.”

A new email: not from the HOA’s general account—from their lawyer. Professional, sharp, conceding: “Ms. Lawson, your submission appears valid contingent upon verification. The board retains its right to inspect implementation. Be prepared to meet the city building inspector, a representative from the fire marshal’s office, and two board members at precisely 7:00 a.m. Thanksgiving morning for a final non‑negotiable compliance inspection. Any deviation—misaligned heater, missing extinguisher, doubtful load calculations—and the event will be cancelled and your terrace access revoked.”

They couldn’t stop me on paper, so they were betting I couldn’t execute overnight. Betting on failure.

It was almost midnight. I messaged Mave: “Move load‑in. Not 6:00 a.m.—now.”

The freight elevator sighed open. A wave of frigid Chicago air rolled into the penthouse. I hit the master switch. A hundred thousand warm‑white fairy lights strung across the greenhouse rafters and the terrace perimeter blinked on at once, casting a soft gold against the pre‑dawn dark. The stainless prep stations gleamed, and the team—my team—began to move.

We had worked through the night. The infrastructure stood exactly as the plan dictated. Heaters positioned, extinguishers mounted, windbreaks secured. One hour to the 7:00 a.m. inspection—sixty minutes to turn a compliant empty space into a living, breathing feast.

Chef Duca arrived at 5:45 a.m., wheeling a battered steel utility cart that looked as if it had seen a war. A crisp white apron over a black chef’s coat. No hello. “Right,” he barked, gravel and authority. “This is not a democracy. This is a kitchen. My kitchen. Lawson—your logistics are adequate.” Highest possible compliment from him. He slammed laminated station signs onto steel tables:

Station 1: Turkey breakdown and roasting—two culinary students on carving. “Don’t let me down.”

Station 2: Potatoes. “We are not making glue; we are making pommes purée. It’s a science.”

Station 3: Gravy and cranberry from scratch. “If I see a can, we’re done.”

Station 4: Root vegetables and soup.

Station 5: Bread and desserts.

He turned my terrace into a culinary battlefield. He was magnificent.

Our partners checked in at the entrance. Mave handed out lanyards I had printed overnight. Not “Volunteer.” They read: “Host + Guest.” A night‑shift nurse named Amelia took hers, still in scrubs, exhausted but bright‑eyed. “Host and guest?” she asked softly. “Exactly,” Mave said with a smile. “We’re all both.” Amelia nodded, tied on the badge, and went straight to the vegetable station—dicing carrots with the speed of a surgeon.

Big Mike—a Falcon Route night driver built like a refrigerator with kind eyes—tapped the sign‑in sheet. “Boss, looks complicated. Where do you want the heavy lifting?”

I pointed to the welcome station. “Right there. Mike, you’re not lifting—you’re organizing.” He looked confused until he saw the pile: wool socks, fleece‑lined scarves, $100 fuel cards, $50 coffee cards. He and two drivers began arranging them like a fine display.

My role wasn’t cooking; it was flow. I stood at a central console—a tablet running my software. “Mave,” I said, pointing at the freight staging area. “Raw ingredients in through Alpha, to prep, to the cooking line—electric roasters and induction burners. From the line, plated food to distribution tables here and here—that’s our last mile. Guests are served. Reverse logistics: bus tubs back to the wash station by the service door. Wash, reset, repeat.” An assembly line. A system. Trust the system; no one gets overwhelmed.

It was working. The once‑cold terrace thrummed with coordinated energy. A teenage violinist set up near a patio heater. Jackson, my security lead—a retired U.S. port guard with an aura of quiet authority—checked windbreak seals. He nodded at the kid. “You gonna play that?” The boy flinched. “Uh, yes. Bach.” Jackson studied him, then smiled. “Good. Play those scales nice and loud. Helps the pies cook faster.” The kid laughed and set his bow.

In the greenhouse—now warm and humid—a different station simmered: a massive pot of mulled apple cider, thick with cinnamon, cloves, allspice. The aroma cut through steel and snow, blending with brown butter, rosemary, thyme, black pepper, roasting vegetables—a bubble of warmth forty‑eight stories above the sleeping city.

I walked the single unbroken line of tables—no VIPs, no head, no center. I set the name cards myself.

An anonymous text buzzed: “Stop this. You’re making a spectacle and embarrassing the family.” The old accusation—my existence as the problem. I muted the thread. No time for ghosts.

“Boss,” Mave said, pale, tablet up. “Real problem. The inspectors are early. And—worse—the Wisconsin long‑haul group decided to come all the way in. Fifteen extra guests. Seating’s full. I don’t have fifteen more of anything.”

Fifteen more people who had nowhere else to go. I looked at the perfectly arranged terrace, the single line of tables, and thought of my father’s text: Thanksgiving’s full. I smiled. “That’s the point. Roll the emergency heaters from storage. Pull the reserve tables from the freight. Open the contingency supplies.”

Duca, overhearing, brandished a wooden spoon, grinning. “Let them come. A real kitchen always makes surplus. We’ve got enough food for an army.”

We had ten minutes—ten minutes to scale again.

The residential elevator chimed at exactly 7:00 a.m. The clatter softened. The violin paused. The steel doors slid open, framing four figures like a civic tableau: the city building inspector with a heavy clipboard; the fire marshal, young and sharp; Mr. Thorne, the building’s counsel in a perfect suit; and Mrs. Davies, HOA president—cashmere, pearls, a frosty perfume that seemed to pull heat from the air. She held her clipboard like a shield.

“Ms. Lawson,” Mrs. Davies said, brittle. “It is 7:05. Your inspection team is here.”

“Good morning,” I said evenly. “We’re on schedule.”

Mrs. Davies took in the field kitchens, steel pots, the rows of tables. “This is unacceptable. A fire hazard. A circus.”

Mr. Thorne placed a calming hand on her arm. “We are here for the compliance check,” he said to the inspectors. “Please proceed.”

The fire marshal went first—straight to Duca’s station. “You the chef?”

“I’m the food manager of record,” Duca grumbled, holding a fourteen‑pound turkey.

“Extinguishers?”

“Class K under the prep table. Class K by the fryer. ABC every fifteen meters—tagged, certified last night.”

The marshal checked tags and gauges, measured heater distances to canvas. “Twenty‑four inches,” he said. Code requires eighteen. He walked the perimeter, inspected wiring, returned to the building inspector. “Heaters compliant. Wiring secure. Egress clear. Suppression adequate. She’s clean.”

Mrs. Davies’s jaw tightened. One pin pulled from her grenade. “The weight,” she hissed. “There must be over a hundred people planned. The terrace cannot support it. Gross violation of structural integrity.”

The building inspector looked at me. “Ma’am, the complaint alleges unsafe load.”

“It’s addressed in my submission,” I said calmly, handing him my tablet open to the right page. “Original structural report—reinforced slab rated at 100 lb/sq ft. Our total load is 24.7 lb/sq ft—less than twenty‑five percent of capacity.”

He did the math, looked at the floor, the tables, the screen. “Numbers are correct. No structural violation.”

Two pins pulled.

Mr. Thorne stepped up. “Inspectors are only part of this,” he said, opening his briefcase. “The board retains oversight on community impact. We’ve received three written complaints regarding anticipated noise. I cite Article 12, Section 1—the right to quiet enjoyment. A gathering of this magnitude with amplified music violates the 9 p.m. sound curfew.”

Their checkmate—subjective feeling over objective code.

“A reasonable concern,” I said, “and anticipated.” I picked up a fresh document. “Municipal permit for minor sound amplification, filed last night—temporary exception for low‑wattage, non‑percussive audio for a charitable event. Valid until 10:30 p.m. Our musician is acoustic. Background audio routes through eight low‑watt speakers aimed inward. Permit attached—page sixteen.”

Mr. Thorne’s eyebrow twitched. Mrs. Davies lost restraint. “I do not care,” she burst out. “This is a residential building, not a soup kitchen or a concert hall. We have a right to peace. The board does not approve of this activity. We are shutting it down.”

My twenty‑nine pages were built for this moment. “Interesting phrase—‘inappropriate use,’” I said, my voice low. “That brings us to the binding clause you overlooked: Article 14, Section 1. The right to quiet enjoyment cannot be invoked as a subjective measure to obstruct a properly insured, fully compliant nonprofit event.” I lifted the final piece of paper. “And this is a letter of acknowledgment from the Chicago Night Shift Alliance, a registered 501(c)(3), confirming tonight’s dinner as their official Thanksgiving outreach and this terrace as the collection point for their winter coat drive.”

Silence. The wind whistled. The building inspector packed his clipboard. “From a city perspective,” he said, relieved, “she’s clean. Fully permitted.”

Mrs. Davies looked to Mr. Thorne, panic rising. “Do something. Tell them the board doesn’t consent.”

The lawyer sighed, a deep, expensive sound, and closed his case. “As I advised the board last night,” he said, “our legal position is untenable. Article 4, Section 2 requires a specific breach. The marshal finds her compliant, the inspector finds her compliant, the insurance is valid, the permits are filed, and Article 14, Section 1 supersedes the board’s subjective disapproval. We cannot stop this on technical grounds. The event may proceed.”

The inspectors left. Mrs. Davies remained, fury gone quiet. “You think you’re clever,” she whispered. “Don’t turn this into social media.”

“I’m not interested,” I said. “Tonight we’re turning it into a family.”

Duca roared from the carving station: “All right—back to work! We have a family to feed!” Cheers and laughter exploded. The assembly line kicked into high gear.

My phone buzzed: “Aurora,” my mother wrote. “I’m begging you. Stop this. You’re embarrassing this family.” I silenced the phone and slid it away. I had a dinner to host.

At 6:00 p.m., the residential elevator chimed. An older man stepped out—thin, neat suit, wool cap in shaking hands. His eyes, clouded with age, were bright and terrified. “I think I’m in the wrong place,” he murmured, looking at the invitation Mave had sent. “It says the penthouse. I’m Walter.”

I walked over. “Walter, you’re in exactly the right place.” I took his arm. “Welcome home.” Jackson fetched a heavy wool blanket and tucked it over Walter’s legs near the greenhouse’s warm edge. Walter’s eyes went wet.

The elevator chimed again, and again, a steady stream: two nurses in blue scrubs carrying a foil‑covered tray. “Just got off twelve hours,” Amelia said, voice rough. “We didn’t know what to bring. We made brownies—for anyone who missed dinner last night.” They set the tray on the dessert table—hosts and guests both.

An elderly couple from the tenth floor came next. They didn’t head for the food. They walked straight to me, eyes scanning the terrace. “We received the HOA memo,” the woman said softly. “We were appalled.” The man pulled a small linen‑wrapped package from his coat. “We heard about the chair,” he said. Inside: a hand‑stitched white handkerchief with deep‑blue embroidery in the corner—no initials, just a phrase: For the invisible one. “We wanted to contribute,” the woman said. I placed it on the carved chair.

Then the drivers—fifteen who had made the last‑minute run from Wisconsin—loud, laughing, stamping snow from their boots. “Boss,” one shouted, “this is unreal. We thought we were getting a cold sandwich in the lobby.” They filled the tables, telling stories of black ice and long dark miles. Big Mike pointed them to a salvaged‑oak board near the entrance: WHAT ARE YOU THANKFUL FOR? Stacks of paper leaves and pencils. A bearded driver wrote clumsily with gloved hands, then pinned his leaf: “Grateful not to be eating alone in my cab.”

Within twenty minutes the board was full—leaf over leaf, orange, red, yellow. The sound shifted from setup to celebration. Duca, cup of cider in hand, told a terrible turkey joke; everyone laughed—the laughter of people finally warm and safe. The violinist, sensing the turn, finished his solemn Bach and slid into a familiar folk song. A few hummed. An older nurse began to sing, shy at first: “Almost heaven, West Virginia…” Walter joined in, thin but clear: “Blue Ridge Mountains, Shenandoah River…” By the second chorus, the entire terrace was singing—nurses, drivers, students—“Take me home, country roads.” No phones. No filming. Just voices, under American winter sky.

Jackson slipped away to the cocoa station Mave had set for the children. He stirred a mug, dropped in three marshmallows, and brought it to Amelia’s six‑year‑old, who sat at the drawing corner beside the gratitude board. “Here you go, little boss,” he murmured. She had pinned her own leaf at the bottom: “Thank you for someone remembering me.”

I refilled cider, adjusted a strand of lights, and watched—Walter telling a story to a med student, Big Mike showing photos of his kids to the elderly couple, Duca high‑fiving Amelia over a perfect slice of turkey. My eyes were wet; the cold dried the tears before they fell. I wasn’t sad. I was optimized.

Another text from a blocked number: “What a performance. You must be proud of your little show.” Delete. Noise removed.

Noah sent a photo—my parents’ dining room: polished mahogany, good crystal, my father at the head pouring wine, my mother smiling, Sloan in the center between two partners from her firm—“Family only,” Noah captioned. I zoomed in. An empty chair—perfectly set—between Sloan and a partner. Their table was “full,” but not complete. I laughed quietly—the same laugh as when my father texted earlier.

“Boss,” Mave said at my side. “Local news picked up the story—off the public portal. They want an interview after eight.”

“No interviews,” I said. “No staged television. If they want to send a camera after nine, they can film service and the coat drive. No mics in faces.”

Mave nodded. “Just the work, not the drama.”

A sharp pop from the kitchen. A flash of blue from the main bank of electric roasters, and the digital display went black. The oven died. Silence. Duca, holding two trays of potatoes, didn’t flinch. “We’re down. Bay Two—reserve roaster online. Move. Two birds cold—we need heat.”

“I’m on it,” I said. “Circuit reset. Five minutes to preheat.”

Duca grinned. “Plan B is your specialty, Lawson.” He turned to the watching crowd and shouted back into the kitchen, “Because we just started Plan B!”

(End of Part 1.)

Part 2

(Chicago, Illinois, USA — the same night, rooftop greenhouse terrace.)

I didn’t start the buzz. The story leaked without my permission—like these things do, not with a bang but with a click. A guest—a medical student I didn’t know—snapped a photo. Not of food or skyline or a selfie. He captured the table: the single, unbroken line glowing under the fairy lights, stretching almost the entire length of the terrace. A geometry that shouldn’t have fit in the city. He posted it in a private Chicago forum with a simple caption: The Long Table—no extra chairs.

By itself, that would have faded. What happened next broke the dam. Ms. Petrova, the building’s night manager—famous for citing doormats as fire hazards—saw the post. She answered to the HOA. I assumed she’d be an enemy.

At 8:00 p.m., the elevator chimed and she stepped out in a crisp uniform. She didn’t speak to me. She stood by the door for five long minutes, scanning everything: Jackson helping Walter to his feet, Amelia’s little girl pinning a paper leaf to the gratitude board, Chef Duca handing a generous slice of pie to one of the doormen on his break. She took it in like an auditor. Then she turned, rode the elevator down, and disappeared.

Ten minutes later, Mave tugged my sleeve, pale. “Boss, you need to see this.” The forum was on her screen. Ms. Petrova had replied to the student’s photo—publicly: I am the night shift building manager. I have worked in this tower for eleven years. I have seen million‑dollar political fundraisers and holiday parties that were full of cold food and colder people. I just went up to review this ‘security risk.’ I saw a retired veteran treated with dignity. I saw a nurse off a twelve‑hour shift laugh until she cried. I saw the staff I work with every day served real pie by a world‑class chef. Mrs. Davies and the board do not speak for the staff of this building. This—this is what neighbors are supposed to be.

A match to gasoline. Someone screenshotted the photo and comment and posted them to a city blog. From there to social. Then everywhere. The hashtag never mentioned a feud or a penthouse. It was simpler: #SeatForEveryone.

By 8:30 p.m., the local news ran a piece—exactly as I’d insisted, with no interview and not even my name. The anchor’s voice was warm, respectful: an anonymous resident in a downtown high‑rise, after being told her family’s table was full, hosted a dinner for 150 strangers on her rooftop—night‑shift nurses, long‑haul drivers, and anyone else who had nowhere to go. The story was spreading.

My phone, face‑down on steel, buzzed so hard it sounded like an alarm. Noah: A, what did you do? My feed is blowing up. That roof photo. The manager’s comment. Someone tagged Mom. She’s losing it.

What did you do? Not This is amazing. The old indictment. I inhaled, and a new text appeared below his. My mother: What do you want from us, Aurora?

What did I want? The truth spilled into my thumbs: A seat. I pictured the metal folding chair, the cold pie, the “family only” photo with its perfectly set empty place. I deleted it. It was too late. I didn’t want a seat at their table anymore. It was too small and too cold. I typed two words—the same two I’d sent my father: Enjoy your meal.

At 8:45 p.m., the weather turned. The wind shoved the terrace hard, snapping the heavy canvas windbreaks like sails. Fairy lights flickered. A sweep of pellet‑hard snow rattled the glass.

The elevator chimed. Not freight—residential. Carlos from the front desk stepped out, cheeks red with embarrassment. “Ms. Lawson, I’m so sorry. The board just called. Noise complaint.”

I looked at my watch. “It’s 8:46, Carlos.”

“I know, ma’am. They said it’s anticipatory—for the 9:00 p.m. curfew. They demand all music off immediately.”

The guests hadn’t heard; they felt the tension. The soft guitar suddenly seemed loud. “Thank you, Carlos,” I said. “You’re doing your job.” He retreated.

I went to the small mixer. I didn’t kill the sound. I lowered the volume, cut the treble, lifted the bass and mids. The music didn’t play so much as hum—warm, like a heartbeat underfoot.

At 9:00 p.m., the news crew arrived: a reporter I recognized from the 10 p.m. broadcast and a cameraman. She was all business. “Ms. Lawson, we’d love your side—the HOA, your family. What’s this really about?”

“No,” I said.

She blinked. “No?”

“No interviews. I’m not the story. This table isn’t about me or a feud.”

“Then what is it?” she asked, frustrated.

“Them.” I gestured to the crowd. “If you want a story, talk to them—film the work, not the drama.” I walked away.

She pivoted, professional again. “Okay—B‑roll. Lights. Food.” The camera light flared—exactly as Walter rose, glass of cider in his trembling hand. He tapped a spoon.

“Excuse me,” he said, voice shaking but clear. The terrace quieted. The camera swung toward him; the light landed on his lined face.

“My name is Walter. I live on the eighth floor. My wife, Eleanor—” he swallowed “—she passed six years ago. She loved Thanksgiving. She always set an extra plate. ‘There is always room at the table, Walter. Always.’ This is the first Thanksgiving I haven’t been alone since she died. I almost stayed home, but I got an invitation.” He looked at me. “And when I arrived, this young woman said, ‘Welcome home.’ Tonight I was seen. Eleanor would have loved this—loved all of you.” He raised his glass. “To Eleanor. To the unseen. And to the long table that found us.”

The roar that followed wasn’t polite applause; it was thunder—nurses, drivers, students on their feet, cheering Walter. The cameraman stayed on him, panning tears and laughter. The reporter stood still, microphone forgotten. She had her story.

That clip—Walter’s toast—led the 10 p.m. news. It hit the internet before the broadcast ended. Comments poured in: I’m crying. Who is Walter? He never smiles in the elevator. He’s smiling. Forget the HOA—this is the story. If your house is full, Chicago has a place. The hashtag was national now.

Mave appeared, ice in her voice. “Boss, you need to see this.” Sloan had posted a perfectly lit selfie from my parents’ dining room—crystal glass raised, mahogany gleaming, the empty chair just visible. Text overlay: Some people make everything a performance—weaponizing kindness.

Mave’s jaw set. “We leak the texts. Your dad’s ‘table’s full’ message. The ‘family only’ photo. We can bury this in five minutes.”

I locked the phone. “No.”

“Aurora—”

“Let the table talk, Mave. It’s saying everything we need.”

The night exhaled. 9:30 p.m. My console phone rang—an actual ring I’d forgotten to silence. I answered. “Lawson.”

A television murmured in the background. Then a sharp, familiar voice—cut glass. “Aurora. This is your grandmother, Martha. I’m watching the ten o’clock news. Turn your television off and tell me exactly what those imbeciles on your board did—and then what your mother said.”

“Grandma?”

“I called the house. Beth and Richard aren’t there. Sloan isn’t answering. After that sad little post, they’re on their way to manage you, I assume?”

I hesitated. “Yes.”

“Of course. I’m calling my car. I’ll be there in twenty minutes. Do not let anyone leave.”

“Grandma, it’s late. It’s snowing.”

“I’m eighty‑two, not made of sugar. I taught constitutional law for forty years. I’m not afraid of snow, a flustered association, or your mother. And I am not taking an app car. I want the Lincoln—the long one. It makes a statement. See you in twenty.” She hung up.

We were in the warm, fading phase. The news crew packed up, energized by Walter’s toast and my refusal to be the headline. Duca and the students packed mountains of leftovers for the shelter run. Mave and the host‑plus‑guest team wrangled a growing mountain of donated coats by the door. The city’s 9:30 decibel check came and went—well below limits.

At 9:42 p.m., the front desk buzzed: Carlos, voice pitched high. “Ms. Lawson—there’s a situation. A very large black limousine is blocking the front drive. It’s parked in front of Mr. Henderson’s Bentley.”

I smiled. “It’s all right, Carlos. She’s my guest. Please send her up. And Carlos—my other family members may arrive shortly. Send them, too. All of them.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

The elevator chimed. Mrs. Davies stepped out, thunder on her face—clearly watching the security feed. “This is the final straw. Lawson, this is a residence, not a hotel. You cannot have commercial vehicles—”

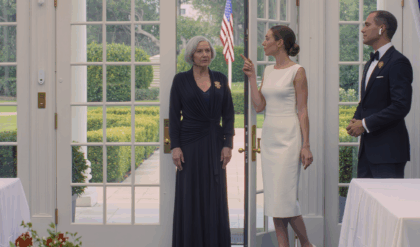

The elevator chimed again. She turned. The doors slid open. My grandmother, Martha Lawson, stood there—five‑foot‑three and commanding the space like a giant. Floor‑length deep‑red wool cloak, silver hair in a severe bun, black leather gloves, a simple cane. She looked magnificent—like a queen.

She stepped onto my marble floor, cane clicking, eyes sweeping from Mrs. Davies to the terrace, the lights, Walter with his coffee. “So,” Martha said, voice carrying through the cold air, “this is the table.”

Mrs. Davies recovered. “I’m sorry, madam. This is a private event—past capacity and winding down. The resident is in violation of—”

“Are you Mrs. Davies?” Martha asked, cutting cleanly.

“I—yes. I’m the president of the board.”

“I thought so,” Martha said. “You have the panicked eyes.” She reached into a structured leather handbag and produced a laminated card. “This is my building identification as a partial owner in the real estate investment trust that holds the note on this tower.”

Mrs. Davies’s mouth opened. Martha wasn’t finished. She pulled a second card. “This is my priority access card, which grants me and my guests unrestricted access to common areas for observation.”

“That—that’s not possible,” Mrs. Davies sputtered.

“Oh, it’s very possible.” Martha produced a sealed cream envelope with a law firm seal and handed it over. “This is a letter delivered this afternoon to Mr. Thorne, your counsel. The Martha and Arthur Parker Foundation finalized acquisition of a 6.2% stake in the building’s commercial REIT at 4:00 p.m. yesterday.” She smiled, a thin legal smile. “I have every right to be here—to attend meetings, review minutes, and observe community events. Especially ones so newsworthy.”

Mrs. Davies went ashen.

The elevator chimed a third time. I didn’t need to look; the air changed. My father, Richard. My mother, Beth. My sister, Sloan. They weren’t here to celebrate or apologize. They were here for damage control. Sloan’s face was a mask of cold fury, phone clenched. My father looked tired and angry. My mother looked ill—eyes darting from me to the cameras to the guests—then landing on her mother.

“Mother?” Beth whispered. “What—what are you doing here?”

Martha turned slowly, taking in her daughter, son‑in‑law, and star granddaughter. “I’m here, Beth,” she said, voice terribly quiet, “because I was also not invited to your dinner. It seems your table was full for me, too.” She held Beth’s gaze. “When exactly did you start excluding me from the list?”

Beth flinched. “It wasn’t—it was business. Sloan’s partners. Complicated. We were going to have you over Sunday.”

“Ah, yes,” Martha said. “The Sunday table. The folding table. The ‘maybe next year’ table. I know it well.”

Sloan stepped forward. “Grandma, this is outrageous. You’re siding with her. She’s making a mockery of this family. She leaked this—”

“She did no such thing,” Martha snapped, not even looking at Sloan. “I’ve been watching. She did the one thing this family forgot how to do—she built a better table.”

My grandmother crossed to me, cane thudding softly on stone. She placed a gloved hand on my arm. “You did well, Aurora. You used their own rules.” She reached into her bag and drew one more document—not for the HOA, but for me. A notarized page.

“I called my lawyer after Walter’s toast,” she said, voice meant for me yet loud enough for all to hear. The news camera, halfway packed, drifted back and its little red light came on. Martha didn’t care. “This is an addendum to my last will and testament, filed and witnessed at 8:00 p.m. this evening. As you know, my estate is significant.”

Sloan stepped involuntarily closer. Beth went white.

“I have adjusted the trust,” Martha continued, formal as a judge. “All previous distributions are null. The new criterion is simple.” She read, voice ringing with final authority: “All disbursements from the Parker Foundation Trust shall be allocated based on a single provision: Whoever opens their table gets a seat. Whoever uses their seat as a weapon loses their chair.”

A gasp rippled across the terrace—Walter, Duca, Mave listening as if to a verdict.

“Mother,” Beth cried, horrified. “You can’t do this. This is private—you’re making a scene.”

Martha faced her, not angry—just done. “Beth, this—” she gestured to the long line of lights “—is not a scene. This is community. This—” she pointed to Beth, Richard, and Sloan “—this frantic arrival to control optics—is a scene. The scene started with the text. The ‘maybe next year’ you’ve been promising this child her entire life. I’m finished with your scenes.”

My father finally spoke, voice a low growl. “She did this to embarrass us. This whole thing—it’s an embarrassment.”

“No, Richard,” Martha said, pinning him with a look. Then back to me, eyes softening for a heartbeat. “She isn’t embarrassing you. She’s humanizing you—and you’re too proud to see it. You’re angry because her light shows you where yours is broken.” She squeezed my arm. “It’s time this dinner belonged to you.”

She looked at me. “Aurora,” she said, voice soft but final. “You’ve earned this table.”

Sloan lunged. “You can’t. This is coercion. Undue influence. She manipulated you. This entire circus—she leaked it to steal your money.”

Mrs. Davies rallied to her side. “She’s right. This isn’t charitable—it’s a vendetta against her family and the board. We’ve been harassed. That’s grounds—this must be grounds.”

Mr. Thorne looked very tired. He opened his mouth, but another voice cut in—clear and cold.

Mave stepped from the shadows with her tablet. “Since Mrs. Davies has raised intent,” she said, addressing the lawyer and the still‑rolling camera, “this is relevant.”

Sloan hissed, “What is that? You have no right—that’s private.”

“Mave,” I said. “Show him.”

She angled the tablet to Mr. Thorne; the camera caught it. “This,” I said evenly, “is a set of screenshots from our family group chat three weeks ago, provided by my brother Noah.”

Sloan went white. She looked at Noah—who stood apart, face grim, eyes down.

Text on the screen was sharp and undeniable:

Sloan: We must keep Thanksgiving small. This is a networking dinner—partners and spouses only. Clean. Professional.

Richard: Keep it simple. Good for the firm.

Sloan: That means no Aurora. She’ll just be awkward. And definitely no Grandma—she’ll pick a fight about politics.

Beth: I’ll handle it. I’ll tell Aurora we’re full. We can see Mother on Sunday. Avoid a scene.

Mave swiped to an email from Beth to Richard: I’ll text Aurora and say we’re full—it’s simpler and avoids a fight. And I agree—let’s not invite Mother. We’ll see her Sunday.

I didn’t need to read it aloud. The terrace saw it. The camera saw it. Silence expanded.

“This was never a party, Mrs. Davies,” I said, voice quiet and dangerous. “It was a response. My father texted, ‘Thanksgiving’s full.’ As you can see, that was not casual. It was coordinated, documented exclusion. Not just of me—but of your own eighty‑two‑year‑old neighbor.” I swept an arm across the tables. “This event—this is the charitable act. The only vendetta here is the one my family and this board wage against anyone who doesn’t fit the ‘clean, simple, full’ list.”

Mr. Thorne took a breath like a man surfacing. He straightened his cuffs and addressed his client. “Mrs. Davies, as I advised in my memo last night, our position was—and is—untenable. This new evidence shifts the matter from bylaws to potential discriminatory enforcement. The board cannot be seen applying rules in a biased manner. We cannot obstruct a fully compliant, fully insured, and now publicly documented charitable event.” He turned to me, clipped. “We are done here. We must retreat.”

Mrs. Davies stammered, grasping for one last anchor. “The health—the safety—the food—”

“I was waiting for that.” Martha stepped forward again, eyes bright with the thrill of a clean argument. She unfolded a faxed page. “One hour ago, my attorneys contacted the county’s emergency certification line. They reviewed tonight’s inspection, Chef Duca’s credentials, and the live broadcast. This is their final certification confirming the event meets—and exceeds—public safety standards. They’ve appended the schedule of fines for third‑party obstruction of a charitable food service by a private association.” She smiled, wicked and satisfied. “It is… breathtaking.”

That was the last pin. Mrs. Davies looked from Thorne to me to Martha, finally speechless. She marched into the elevator. Mr. Thorne, ever the professional, sighed once, nodded to me, then to Martha. “Good evening.” The doors closed.

The battle was over. The terrace went impossibly quiet—only the low hiss of heaters and the soft tick of cooling roasters.

My family remained—exposed on my terrain. Sloan stared at Noah, betrayed. My father stared at the floor. My mother cried—silent, messy tears.

Duca broke the spell, wheeling a steel cart between my family and my guests. Ten pies steamed—apple, pumpkin, pecan—the air thick with cinnamon and caramel.

Sloan found her voice, not a roar but a hiss. “You planned this. All of it. The camera. The screenshots. The will. A trap.”

Before I could answer, Noah stepped forward. The diplomat left the middle. He put a hand on Sloan’s arm. His voice was quiet but heavy. “Sister—stop. Just stop and listen. For once, listen.”

Sloan recoiled as if struck. Her neutral ground had picked a side.

I walked past them to my chair—the carved oak armchair. I set my hand on the back and traced the letters: For the one who felt unseen.

“I don’t need a seat at your table anymore,” I said. The anger was gone. I felt empty—and clear. “I don’t need your approval or permission. I’m not asking you for anything.” I turned from the chair to face them. “I just need you to stop taking seats away from other people.”

My grandmother stepped beside me, her gloved hand resting on the chair next to mine. She looked at the guests, then at the small, respectful news camera, and read the words carved in the wood aloud. “For the one who felt unseen.”

Walter stood, empty coffee cup in hand. “Tonight,” he said, voice carrying in the stillness, “I was seen.”

My mother made a small choking sound. “Aurora,” she whispered, lost, a child again. “I didn’t mean—I didn’t know. I was just afraid it would be… messy.”

My grandmother turned to her daughter, sadness deeper than anger. “Messy is better than empty, Beth.”

I looked at the trio—the star attorney silenced, the executive staring at his shoes, the perfect hostess crying. I breathed. The air was cold and finally clean.

I turned away from them—to my family: Walter and Amelia’s sleeping daughter, Big Mike, Mave, and Duca. “Dinner continues,” I said.

Duca plunged a silver server into a pumpkin pie—thunk. The violinist lifted his instrument and drew one long, crystal note that hung in the frozen air like the sound of a lock turning.

Snow thickened—soft, cinematic flakes layering the glass roof, blurring the sharp stars. Downtown became a hazy glow. The terrace felt like a snow globe—its own small world.

Martha stepped into the open space between tables. “Young man,” she called gently to the violinist, “may I borrow your microphone—the little clip?” He handed her the tiny condenser mic. She took a glass of cider—not to tap, but to hold.

Her gaze swept first over my family—clinical, assessing—then to Walter, Big Mike, the tenth‑floor couple, and the respectful camera. When she spoke, her voice was only slightly amplified, heavy with final judgment.

“Tonight, we learned a lesson in architecture,” Martha said. “Some tables are fortresses—polished, cold, and in the end, empty. And some tables are bridges—long, warm, and full.” She turned as if to speak to the whole city. “As the newest stakeholder in this building’s managing trust, the Martha and Arthur Parker Foundation pledges a ten‑year grant to fund this penthouse long table as an annual Thanksgiving event for Chicago—professionally catered, fully staffed, open to all.”

A gasp, then applause—Duca and Walter first, rolling outward.

Martha lifted a hand for quiet. “Furthermore,” her eyes found Sloan, “as I informed my family this evening, my will and the foundation charter are irrevocably updated. The terms are simple: Whoever uses their chair as a weapon loses their chair. Whoever uses their chair to invite another—” she smiled, small and fierce “—gets the whole table.”

Sloan’s hand tightened on her bag strap. She had no argument for a clause cleaner than any brief.

I looked to Noah near the greenhouse. He met my eyes and gave one slow nod. The neutral line was gone.

I didn’t look at the camera or my parents. I looked at the one empty chair—the one I’d carved. I placed my palm on the letters. The wood felt like a scar finally healed—no longer tender, just structure.

I raised my glass to the guests. “To those who used to stand at the door,” I said, voice clear in the cold. “From now on, this door is open.”

“Cheers!” Walter cried, voice cracking, lifting his cup. The chorus followed—drivers, nurses, students—fairy lights reflecting in wet eyes, even the elderly HOA couple clapping, late but real.

My father stepped forward, mouth opening for a last attempt to reclaim the narrative. “Aurora, I—we—I just—”

No one waited. The violin soared—joyful, defiant—swallowing his words. Duca, laughing, tapped a spoon against a water glass—clink, clink, clink—turning the moment into a celebration.

My grandmother leaned close, voice for me alone under the music. “You see, child? You stopped waiting for permission. You gave permission.”

I looked up. Snow was a white wall now, the glass roof frosted. The city was only a memory of light.

I lifted the carved chair—heavy oak—and carried it to the exact center of the long table. I angled it outward. No one sat in it. It wasn’t for sitting. It was for seeing—a centerpiece, a promise.

The cameraman zoomed in as Martha raised her glass, and I raised mine. Old glass met new with a small, clear clink. Applause rose into the snowy night. It was the only answer that ever mattered.

(End of Part 2.)

Part 3 (Finale)

(Chicago, Illinois, USA — late night, snowfall over the downtown skyline.)

The long, clear note from the violin faded, leaving only the warm hiss of the patio heaters and the soft shuffle of coats being gathered for the drive. Snow drifted thicker against the glass roof, turning the city into a watercolor of gold and white.

We plated dessert. Duca stationed two students on pie service and sent the rest to box up meals bound for shelters across the Loop and Near West Side. Big Mike coordinated the coat mountain like a loading dock foreman—sizes to one side, kids’ items front‑and‑center, heavy parkas stacked by the door for overnight pickup.

Walter stood again, steady now, and slipped his hand along the carved oak chair at the center of the table as if it were a rail on a ship. “For the one who felt unseen,” he read softly, more to himself than to the room. He smiled and took his seat, a man finally at ease.

Noah drifted to my side. For the first time all night, he met my eyes without looking away. “I should have spoken up sooner,” he said. No performances. No negotiation. Just an apology shaped like a fact.

“Then speak up now,” I told him. “Help Jackson load the coats.” He did—no further words needed.

Across the terrace, my mother dabbed at her face with the linen handkerchief the tenth‑floor neighbor had embroidered—for the invisible one. She traced the blue stitching with her thumb, then looked up as if she had only just realized the embroidery wasn’t initials but a sentence. She held the cloth a little tighter and, for once, stayed quiet.

My father hovered near the elevator, hands buried in his coat pockets as if they might find an answer there. He looked at Martha and then at me. Whatever he meant to say dissolved under the bustle of plates and the small, practical holiness of people serving one another. Some speeches are better left unsaid.

Sloan stood apart, phone forgotten at her side, eyes fixed on the carved chair. She looked like someone confronted by a map that finally showed the road she refused to take. Her expression softened—not surrender, not yet—but the first small cracking of ice.

Martha circulated like a judge in chambers, not to scold but to witness: a word with Jackson about the late‑night lobby access for the coat drive; a word with Duca about getting the shelter run a police‑approved loading zone; a word with the elderly couple about attending the next open board session. Wherever she stopped, trouble lost momentum.

At 10:15 p.m., the cameraman—lingering for one last wide shot—lowered his rig and simply stood in the doorway watching, hat in hand. “Ma’am,” he said to me quietly, “I think we got what matters.”

“You did,” I said. “Thank you for keeping it respectful.” No lights in faces. No manufactured drama. Just work.

By 10:25 p.m., the coat drive filled two cargo vans. The shelter trays were labeled and staged. Mave checked off her final boxes on the tablet and turned it toward me: Ingress flow: complete. Egress flow: green. Waste audit: compliant.

“Good,” I said. “Send the first van.”

She keyed her radio. Jackson and Big Mike moved like a practiced crew, guiding the carts to the freight elevator. The violinist tucked his instrument away and, as he passed the chair, reached out and brushed the carved letters with two fingers—an unspoken thank‑you—and then gave me a small bow.

Guests began saying goodnight the way families do—three times each, at the door, then at the elevator, then again when the elevator doors closed and they waved through the glass. Amelia lifted her sleeping daughter carefully, wrapping the child in one of the fleeces. “Host and guest,” she whispered as she passed me. “Thank you for both.”

“You’re always welcome,” I said, and meant it.

The news crew left without a final question. The last of the drivers checked the road report—Lake Shore Drive slick but passable. Walter took a third slice of pie for later and a paper leaf from the gratitude board for his pocket. “To show Eleanor,” he said with a grin, stepping into the elevator as the doors glided shut.

The terrace exhaled. Quiet. Just us—Mave, Duca, Jackson, a few students policing the last crumbs, and Martha by the carved chair.

“Tomorrow,” Duca announced, “I will pretend to be retired again.” He pointed a stern finger at me and then softened. “Until next year.”

“Until next year,” I promised.

Jackson clicked off the last battery arrows on the egress markers and rolled his shoulders like a man who could finally put the night down. “Smooth move, boss,” he said. “All lanes clear.”

“Thanks to you,” I told him. He tipped two fingers to his temple and headed for the freight.

Mave lingered. “You sure you don’t want to post?” she asked gently. “Not a victory lap—just the resources for people to replicate this. The vendor list. The permit steps.”

I thought about it—the quiet power of instructions. “Draft it,” I said. “No names. No faces. Just the blueprint.”

“On it.” She smiled, the satisfied smile of an operator whose system worked, and followed Jackson.

Martha and I were the last. Snow stacked against the greenhouse glass in soft ridges. Downtown glowed like a hearth in the distance.

She touched the carved letters again, then looked at me. “It will not fix everything,” she said simply. “But it fixes what it can touch.”

“It’s enough,” I said.

“For tonight,” she agreed. Then, with a glint of her old courtroom showmanship, she added, “And for the record, I did enjoy the Lincoln. Statement made.”

I laughed—a warm, human sound that didn’t need armor. We walked to the door.

At the threshold, I turned back. The long table caught the last of the fairy lights like a river catching starlight. In the middle, the chair faced outward, not waiting for anyone, simply bearing witness.

“For the one who felt unseen,” I whispered. “May they always find the way home.”

We closed the terrace and stepped inside. The heaters dimmed, the glass roof whispered under the snow, and Chicago breathed below us as the night carried the last notes of our small orchestra down to the streets.

—

Postscript (Resources for Community Tables in the U.S.)

To help others build their own inclusive, safe, and compliant community meals in American cities, here is the high‑level blueprint we used (shareable and policy‑safe):

• Identify partners: night‑shift workers, healthcare staff, delivery drivers, building staff, neighbors.

• Confirm venue load ratings and egress; get a licensed inspector’s sign‑off (fire, electrical, wind abatement).

• Secure event insurance appropriate for headcount and cooking/heating equipment.

• File required city/county permits (temporary food facility, minor sound amplification if needed). Use a certified food protection manager of record.

• Design clear flow: staging → prep → cook → plating → distribution → bus/wash → waste audit. Keep aisles wide and marked.

• Warmth & dignity: wool blankets, socks, fuel/coffee cards, “Host + Guest” badges so everyone serves and is served.

• No “kids’ table”: create a drawing corner or activity space integrated into the main area.

• Privacy & media: prioritize consent; if press is present, focus filming on the work and resources—not private drama.

• Aftercare: box leftovers for shelters; coordinate late‑night lobby/loading with building management.

Thank you for reading. If this story moved you, consider supporting local shelters, driver relief funds, and nurses’ unions in your city—quietly, consistently, and with an open seat at your table.

(End of Part 3 — The End.)